Why this artist used seesaws to protest at the border

For about 40 minutes, three pink seesaws bobbed up and down, up and down, along the U.S.-Mexico border, uniting children from both countries in a rare moment of shared play.

The art installation — steel beams installed through part of the border fence that separated Juárez, Mexico, and a desolate area of Sunland Park, New Mexico — was temporary. But the videos and photos of the moment helped spread an enduring message of harmony and solidarity at the border.

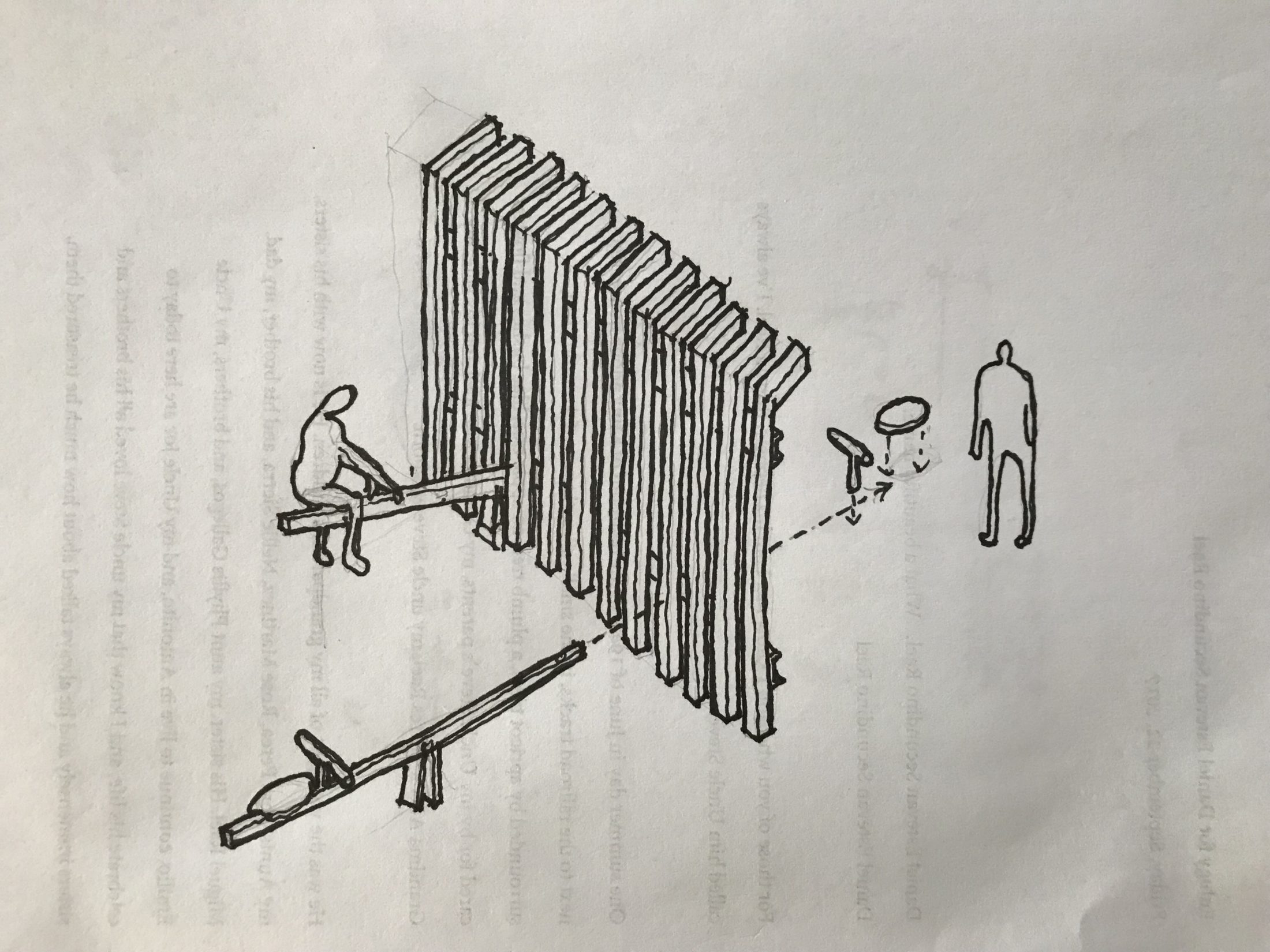

The project, titled "Teeter-Totter Wall," was a decade in the making. Early conceptual drawings of the idea sprang from the partnership between U.C. Berkeley architecture professor Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, associate professor of design at San Jose State University.

Drawings for the art piece from 2009 were a reaction to the 2006 Secure Fence Act, which led to the eventual construction of about 650 miles of barrier along America's southwest border. Rael published those conceptual images in a 2017 book called "Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary." In July, when the architects turned the idea into a reality, the project's protest message morphed into a critique of U.S. immigration policy under President Donald Trump.

The seesaws, too, embody the juxtaposition of play and violence. Rael told the PBS NewsHour that the seesaws were rendered this specific shade of pink partly because the color has a deep connection to Juárez, where it's used to remember women who have died from violence since the early 1990s.

Over the years, one part of the message has remained constant. The seesaw is a "reminder that the actions on one side have consequences on the other," Rael wrote on Instagram.

The PBS NewsHour followed up with Rael to ask how he built the art piece, how its meaning has changed under different administrations and how play is a form of protest.

The drawings for the "Teeter-Totter Wall" became a reality 10 years after they were first designed. How did this day come together?

The day itself may have started in 2016 when we had decided that we could actually do this on the border, make it a reality. We asked for permission several times from Border Patrol agents. We tried to collaborate with many arts organizations along the border, but the answer is always no. And it came to a point when we decided that it didn't seem like this was illegal, and we simply decided to do it.

And so, the night before, we went out to look at the site, everything was ready, all the teeter-totters were built and had been tested. We went out there. The children gathered as they always do. And we asked them, "Well, what do you think if we put some teeter-totters here?" And they thought that'd be cool. And so, we'll be back tomorrow afternoon.

The next day, we just showed up, and we knew there'd be a lot of people on [the Mexico] side because the village pushes right up against the wall. But we did invite people from the U.S. side because it's fundamentally a desolate area on [that] side.

Did you get a reaction from Border Patrol agents when you did this?

When we actually did it, Border Patrol showed up maybe in five minutes of us starting the event. And they simply drove by. They asked us what we were doing. And so, on the U.S. side, we explained to them what was going on. And they said, "How long will this take place?" And we told them. And they said O.K. And so they pulled their truck over, and they just watched. In fact, they were invited to participate.

Same on the Mexican side — I was on the Mexican side — soldiers came by, and they also asked what was going on. And we told them. They smiled, they took out their camera, and took some pictures. They [sat] back and watch[ed] for a while.

Did either the Border Patrol agents or the Mexican officers participate on the seesaws?

No, they didn't. But wouldn't it be great if we could have gotten a Border Patrol agent and a soldier to ride the teeter totter together?

What message did you want to send?

There are plenty of metaphors in art that one can attempt to communicate. And I'd like to think that if it's good art, then people can derive their own messages from that expression. But certainly — in their conception early on, even before we built them, but in drawing form — they spoke to issues of inequality, of separation, of balances, the kinds of words that one would use when talking about trade balances, let's say, or labor balances or inequality, racial inequality, or inequalities of wealth and poverty. And so, all these kinds of dichotomies are present in the teeter-totter: sharing, community, collaboration, generosity. These are all aspects of what one feels when they are on a teeter-totter. You have to give, and you take, and there is this relation. The actions that take place on one side have a direct consequence on the other.

In my book, "Borderwall as Architecture," I mention that the border has become a scar. The aerial view from above made the teeter-totter look like stitches or sutures, kind of mending that scar, and that wasn't my intention to do that — or Virginia's — but that's something that has come up several times by others when they see [the seesaws]. It's a sutured wound.

The seesaw is also associated with childlike joy. Why was that vital to your message?

Many of the conceptual drawings that we did for the book communicate the idea of play. And play is, in many ways, a form of resistance. It's often seen as a resistance to authority, and it's done in a very innocent way. The work is an act of protest, but we were not out there with picket signs. We were not out there stating particular messages of resistance. We were demonstrating how the act of play, the act of engaging that place, was our act of resistance to say that, "This is our place," and we can dismantle the meaning of the wall and its violence.

The drawings for the "Teeter-Totter Wall" first emerged early into former President Barack Obama's first term. Were there any particular ideas at the time that you wanted to communicate about migration or borders then?

What was going on then was that much of the wall — that was passed in [former President George W.] Bush's Secure Fence Act of 2006 — was being constructed. It was very important for us during that time that there was a message being communicated about the problematics with the construction of this wall. And certainly Obama had an enormous number of deportations during his administration and construction of the wall. What's also interesting is that that particular stretch of wall, in which we installed the teeter-totter, was constructed in the Trump era. But it wasn't a wall that was constructed, as far as I understand, through any acts that he put in place. This was all left over from the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which mandated 800 miles of wall. And so, this is funding that comes from a much earlier administration. Prior to that, it was a chain-link fence there.

All this is also a reaction to the enormous costs of the wall itself. In the book, we talked a lot about how very simple acts diffuse those kind of budgets or, let's say, military research that you could spend millions of dollars to create a wall and then someone on the other side could just lay two ramps and drive over it, or dig a tunnel under it, or stick a teeter-totter through it. And part of the message, again, that we're communicating is that, this isn't, in some ways, a kind of war game where the technology gets greater. In fact, the smaller technologies become more innovative. Whether you're a bird or a rainstorm or a human, there will be ways to transcend this wall. Is this a solution to immigration? These are the questions that we're asking with this work.

Has your critique or message changed under Trump?

Yes, in fact, I think it has, because what happens in Trump's immigration policy is the separation of families and the separation of children from their parents. And I think that gives much more impact to the nature of that particular work, because we now see children playing at the border and we understand the humanity of those children. I think that's what's been largely absent in the acknowledgement of the consequences of separating children from their family: the enormous psychological and emotional damage that is being placed upon these children.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.