6 Dr. Seuss books will stop being published because of racist imagery

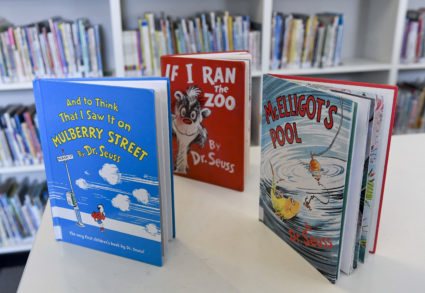

BOSTON (AP) — Six Dr. Seuss books — including "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street" and "If I Ran the Zoo" — will stop being published because of racist and insensitive imagery, the business that preserves and protects the author's legacy said Tuesday.

"These books portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong," Dr. Seuss Enterprises told The Associated Press in a statement that coincided with the late author and illustrator's birthday.

"Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises' catalog represents and supports all communities and families," it said.

READ MORE: 'I am not a virus.' How this artist is illustrating coronavirus-fueled racism

The other books affected are "McElligot's Pool," "On Beyond Zebra!," "Scrambled Eggs Super!," and "The Cat's Quizzer."

The decision to cease publication and sales of the books was made last year after months of discussion, the company told AP.

"Dr. Seuss Enterprises listened and took feedback from our audiences including teachers, academics and specialists in the field as part of our review process. We then worked with a panel of experts, including educators, to review our catalog of titles," it said.

Books by Dr. Seuss — who was born Theodor Seuss Geisel in Springfield, Massachusetts, on March 2, 1904 — have been translated into dozens of languages as well as in braille and are sold in more than 100 countries. He died in 1991.

He remains popular, earning an estimated $33 million before taxes in 2020, up from just $9.5 million five years ago, the company said. Forbes listed him No. 2 on its highest-paid dead celebrities of 2020, behind only the late pop star Michael Jackson.

As adored as Dr. Seuss is by millions around the world for the positive values in many of his works, including environmentalism and tolerance, there has been increasing criticism in recent years over the way Blacks, Asians and others are drawn in some of his most beloved children's books, as well as in his earlier advertising and propaganda illustrations.

The National Education Association, which founded Read Across America Day in 1998 and deliberately aligned it with Geisel's birthday, has for several years deemphasized Seuss and encouraged a more diverse reading list for children.

School districts across the country have also moved away from Dr. Seuss, prompting Loudoun County, Virginia, schools just outside Washington, D.C., to douse rumors last month that they were banning the books entirely.

"Research in recent years has revealed strong racial undertones in many books written/illustrated by Dr. Seuss," the school district said in a statement.

In 2017, a school librarian in Cambridge, Massachusetts, criticized a gift of 10 Seuss books from first lady Melania Trump, saying many of his works were "steeped in racist propaganda, caricatures, and harmful stereotypes."

WATCH: Reevaluating 'To Kill a Mockingbird' 60 years later

In 2018, a Dr. Seuss museum in his hometown of Springfield removed a mural that included an Asian stereotype.

"The Cat in the Hat," one of Seuss' most popular books, has received criticism, too, but will continue to be published for now.

Dr. Seuss Enterprises, however, said it is "committed to listening and learning and will continue to review our entire portfolio."

Numerous other popular children's series have been criticized in recent years for alleged racism.

In the 2007 book, "Should We Burn Babar?," the author and educator Herbert R. Kohl contended that the "Babar the Elephant" books were celebrations of colonialism because of how the title character leaves the jungle and later returns to "civilize" his fellow animals.

One of the books, "Babar's Travels," was removed from the shelves of a British library in 2012 because of its alleged stereotypes of Africans. Critics also have faulted the "Curious George" books for their premise of a white man bringing home a monkey from Africa.

And Laura Ingalls Wilder's portrayals of Native Americans in her "Little House On the Prairie" novels have been faulted so often that the American Library Association removed her name in 2018 from a lifetime achievement award it gives out each year.

AP National Writer Hillel Italie contributed from New York.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.