In zines, LGBTQ creators find a place to tell their own stories

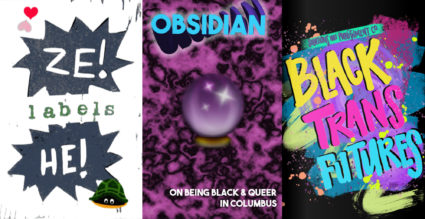

When Dkéama Alexis and Ariana Steele wanted to create a space specifically for Black queer and trans people in central Ohio, they began with a simple but powerful medium: a zine. Named after a "very protective stone," "Obsidian" was the first title released by the Black Queer and Intersectional Collective (BQIC) in 2017, Alexis said.

For their project's namesake, "we chose these black stones to emphasize the preciousness of Blackness, as well as bringing an additional element of our people needing healing and protection," Alexis said.

Somewhere at the intersection of the academic essay, a diary entry, a self-portrait and a notebook doodle exists the zine — a DIY publication usually made without financial profit in mind. This genre of personal expression has long been a powerful tool of political education, an outlet for those whose stories and images have been buried, distorted and regulated by those in power.

Zinesters create out of a desire to share their art and experiences with each other. Although they have existed for nearly a century, zines are best known for their roots in punk and DIY underground subcultures. And among counterculture movements and marginalized communities — without the restraints of gatekeepers — zines can be their own authentic and unaltered statement of self.

To become a budding zinester, all you need is scissors and paper, something to write, draw or type with, and something to express. Creation in hand, you head to a local print shop or library to make copies. Lastly, you decide how you want to distribute it — attend a local zine fair, post online, hand copies out to friends or keep it for yourself.

Among queer communities, zines can be a form a documentation, a capturing of U.S. history that may not appear in textbooks. For their zine, the two BQIC founders collected visual art and poems from seven black queer and trans artists in Columbus. The result is a snapshot of these lives: the love, pride, fear, strength and beauty. To Alexis, being entrusted to share such vulnerable narratives felt invigorating.

Zines are a way to "reflect each other's pains and triumphs back at each other," Alexis said. "It is very restorative and regenerative."

One week after the "Obsidian" release party, police pepper sprayed and arrested four Black queer activists at the city's Pride parade. The aftermath of the incident led BQIC to create the first-ever "Community Pride" events to center the voices of Black and brown queer and trans people, which included a new, separate zine called "Onyx."

On page 4 of "Onyx," BQIC's second zine that was released in 2018, all-caps text says that "ordinary people can make extraordinary things under the right pressure."

To Alexis and Steele, who said they had confronted transphobia, homophobia and racism among various local activist communities, making a zine wasn't just about self-expression, but felt essential as a tool for organizing for and with Black queer, trans and nonbinary people. It became a "very powerful avenue for learning and teaching," Alexis said.

"There's a really certain type of story that gets told in [the] media and it takes a lot to go around that if you don't have access, prestige, if you're not the 'right' skin color, if you don't have the 'right' economic background," said Milo Miller, co-founder of the Queer Zine Archive Project. "And zines take all of that and say, 'To hell with that.'"

Founded in 2003, Miller and Christopher Wide's archive project grew from their personal collection of 25 zines to over 2,500 made by LGBTQ folks spanning five decades.

"They're just human stories," Miller said. "They are people falling in love, they are people having sex, there are people doing drugs, they are people who are politically involved, they are people who are politically not at all involved."

Miller, who uses the pronoun they, published their first zine in 1992, nearly a decade into the HIV/AIDS epidemic. To them, it was a platform to freely share sex education information (like how to put on a condom) with queer teens, for whom there were not a lot of resources. During the early years of the crisis, when government and news organizations were largely silent, zine-making in the LGBTQ community had become more vital than ever, communicating and documenting queer stories of living with and dying from the virus.

"When you're being ignored and your health concerns are being ignored, the only people that you have to turn to are each other, and — from an information-sharing standpoint — zines certainly played a huge part in that," Miller said.

For future generations, Miller believes that zines created in 2020 will provide a similar window into the lives of LGBTQ people disproportionately affected by both the coronavirus pandemic and systemic discrimination.

"Because it's in print and because you control it, there is a good chance that those stories and those zines will be preserved," Miller said.

According to Hunter Shackelford, a Black, nonbinary writer and artist who uses the pronouns "she" and "they" interchangably, zines continue age-old traditions of storytelling meant to uplift a community, a means of survival for marginalized groups. That is why, even with the internet and social media, zines are still here, providing a unique platform for art and activism, and everything in between.

Fat politics, the construct of gender, and black trans futurism are a few of the subjects Shackelford has covered.

Their latest zine, "Before They Kill Me First," highlights the death and violence experienced by Black trans people at the hands of Black cis men. It's a conversation they feels is overlooked within the Black community, and, to prevent it from becoming a narrative used to further stereotypes and anti-Blackness, one that Shackelford says Black people should have with each other.

At least 21 transgender or gender nonconforming people have been killed by violence so far in 2020, according to Human Rights Campaign. In response to some of those deaths — of Dominique "Rem'mie" Fells, Riah Milton, Nina Pop and Tony McDade — tens of thousands rallied in Black Trans Lives Matter protests across U.S. cities, and resources on supporting Black trans lives inundated social media. To Shackelford, while such awareness-raising events are positive at the surface level, the way these stories are framed can become a violence of its own.

The trans community can "become obsessed with trauma because we realize it's the only thing that other people can hear," Shackelford said, noting that focus limits "the joy that we share out loud."

For Shackelford, zines created by trans people for each other often aim to balance both trauma survival but also that joy.

"I want to impact people deeply with storytelling, I want them to feel the story moving through their blood, through their bones when they read it," they said. "What I hope from the zines is that I can again add to Black trans histories and also keep building Black trans futures."

Bay Area zinester Jackson Stoner released his latest zine, "Gender Euphoria," amid the COVID-19 pandemic. It's the eighth issue in his recurring series "Transvestia," which was named for Transvestia magazine, created by Virginia Prince in the 1960s to provide education and representation on gender fluidity. In Stoner's work, the art and text inside call out dominant cultural narratives that commodify trans pain and think of trans people only as an "other."

Stoner, who uses the pronouns "ze" and "he" interchangeably, said that the prevailing media make "trans people's lives seem like it's fraught with only violence and sadness and dysphoria, and focus everything on medical transitioning and surgeries and looking as cis as possible." To him, the solution is not to avoid the real stories of violence or trauma, but to imbue them with "a holistic view of that person's life."

As Miller put it, "We have a sense of history, whether it's the U.S. history or world history or LGBT history, that is made up of permitted documentation," such as newspapers or birth certificates. But zines "tell the stories that don't necessarily end up in the history books and in the classrooms, but are no less valid."

Stoner's zines focus on the intersections of many different identities, including life with a disability, religion, gender and sexuality, in the hopes of creating a shared sense of community and understanding.

In the zine "labels," Stoner writes how categories such as gender pronouns and sexual orientations can both draw people together — "there is family and understanding in connection in our labels" — but also be too restrictive.

"When we choose not to use labels for ourselves," the zine reads, "we are giving ourselves the power and freedom to explore and find new meanings."

For "labels," Stoner decorated the zine with stamps and stickers — turtles, frogs, a sloth that's saying "Don't care" — to bring his personal touch of joy to each reader.

A zine is a wealth of possibilities to Stoner and the others: "You can make any content you want," he said.

MORE: How two poets are nurturing support networks disrupted by the pandemic

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that Jackson Stoner is based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.