At 80, Judy Chicago isn't done with the mysteries of life and death

Judy Chicago wants you to know a few things about birth and dying. But first, she wants you to know she's still here.

On her 80th birthday this past month, the influential American feminist artist opened a museum of her work in Belen, New Mexico, the community where she resides. The museum was originally the idea of a former mayor of Belen, but fierce resistance by evangelical residents, who describe her work as pornographic, prevented it from opening for over a year. One local resident told The New York Times he'd "never want to see a vagina hanging on my wall." So, eventually, Chicago opened the museum on her own.

It was a culture clash reminiscent of earlier debates over Chicago's work, which was deemed radical early on for depicting women, and women's anatomy — even in a non-sexualized manner. In 1990, after Chicago announced she was donating her iconic art piece "The Dinner Party" — in which ceramic plates are set at a table to commemorate important women throughout history — to the University of the District of Columbia, the gift sparked angry debate on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. It so incensed former California Rep. Bob Dornan that he cried: "This thing is a nightmare. This is not art, it's pornography, 3-D ceramic pornography!"

And yet Judy Chicago keeps creating work, and has remained ever-timely by tackling ideas not only about what it means to be a woman, but also what it means to be alive.

Her "Birth Project" series from the 1980s, which involves dozens of pieces of needlework and paintings that depict and celebrate the birth process, has been reshown around the country over the last several years, and a selection of it is currently on exhibit at the Harwood Museum in Taos, New Mexico. Her latest work, a new series of painting on porcelain, glass and bronze, called "The End," explores the opposite end of the life cycle by examining her own mortality as well as the extinction of species. It will open at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. this fall.

The PBS NewsHour recently caught up with Chicago ahead of her museum opening in Belen to talk about growing old, what's changed in feminism and in the art world, and why her decades-old pieces feel as relevant as ever.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the significance of opening your museum, Through the Flower, in Belen? Did you expect that reaction from local residents?

The responses of people who live in Belen who have come to the opening have made it clear that some of the very vocal, right-wing people did not speak for this town. It's settled down but I understand that the Calgary Church in Belen is holding a family-friendly event at the precise time we are opening Through the Flower.

And I did not expect it, absolutely not. But what happened afterwards is this incredible outpouring of community support. In fact, last night, at Through the Flower we did a tour for some people and one of the women burst into tears and said, "This is so beautiful."

What's happening here is actually very gratifying because it's a demonstration of what art can be, and what it should be, in my opinion, which is that art should be more broadly available, and especially art to which people relate. It's not just any art — it has to do with making art more accessible to a broader audience. And as you probably know, the art world has gone the absolute opposite direction, where students in art schools are taught to make art nobody understands, that nobody cares about, and couch it in such pretentious language.

Why do you think that has happened?

Between 1999 and 2006, I did a series of residencies around the country and at different types of art schools: high-end, rural, everything from [Western Kentucky University in] Bowling Green to Vanderbilt and Indiana University Bloomington. And what has happened to studio art education — I don't know if it's a function of art moving on to university campuses, after the Second World War, and people feeling like they had to justify art, by doing theory — but kids don't learn how to draw. We did a show in Belen's City Hall recently with local artists, and most did not know how to paint. When I was an art student I painted walls, I built walls. Now they've gotten rid of even things like ceramics.

Let's turn to the "Birth Project," which you made in collaboration with more than 150 needleworkers in the 1980s. It's now being exhibited in part at the Harwood Museum and in other places. Why do you think that series is still so timely?

I did the "Birth Project" in the 1980s, when I got interested in there being so few images of birth in Western art. I had a very diverse audience, and I wanted to provide information to cross audiences. Also, at that time nobody knew anything about birth, which was exemplified by one of the stupidest critiques of the "Birth Project" I ever received, which said that Judy Chicago's "Birth Project" degrades women because it shows them giving birth on their backs. I've been accused of a lot of things, but now I'm responsible for OB-GYN's entire history of women giving birth on their backs? (laughs) There were other critiques. It's funny, I'm turning 80, and I can still get a cis white man to foam at the mouth by my work.

Birth was shrouded in mystery then. Earlier, men were not allowed to be there when women gave birth. And there was so much unknown. Now that's all changed. But the responses to it now are so striking. All the sudden there is so much interest again.

When I visited the "Birth Project" exhibit at the Harwood, I also heard a complaint from a man who said that the exhibit showed the pain of birth without showing the joy. Your "Birth Tear" pieces, for example.

Well, what about the piece "Birth Power," which is reveling in the power of the woman's own body?

A young reporter recently asked my husband about some of the things people say about me, and he said, "Most of it is just not true." What can be said about me at this point? Here's the good thing about being 80 — what at this point can get me really upset? (laughs) My work has been debated on the floor of the House of Representatives by people who have never seen it, and these idiots in my hometown who have never seen it.

I can't control people's responses, and I wouldn't want to. The fact that my work has so much impact and so many people want to see it is what matters.

So are the responses different now from when you originally released it?

Responses are not very different now compared to when it was first shown, which is terrible. I think that's because it's intersecting with this incredible assault on reproductive rights. And that assault is a reminder of the centrality of human birth to the human experience, which makes it seem incredibly relevant.

You also focus in the "Birth Project" on natural birth and how some women at the time were starting to question whether it might be better in certain ways than a hospital birth. This, I think, is something women are still questioning now.

When I did the "Birth Project," I did it in Northern California, which at the time was the center of alternative birth. Since that time, the medical profession has re-medicalized birth by this huge increase in cesareans. I'm glad there is a reaction against that. There are also all these lies around that kind of birth, where women are simply not told what the consequences are of induced labor or an episiotomy.

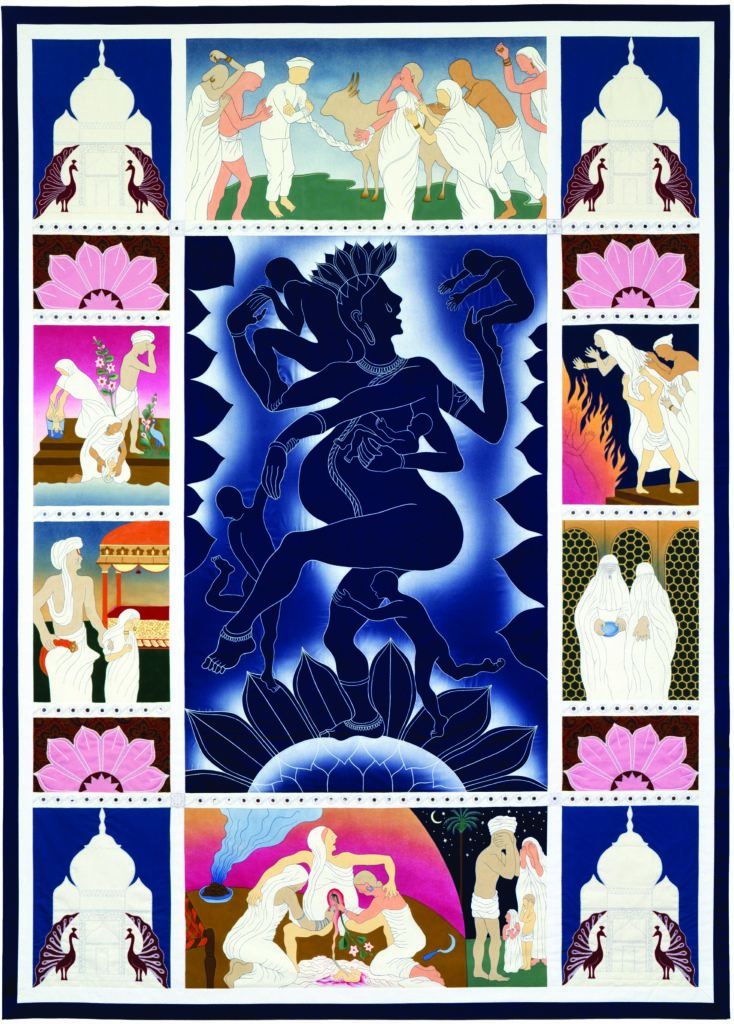

I wanted to ask you about one piece in the "Birth Project" called "Mother India," which contains different panels showing some historic practices affecting rural Indian women, such as forced marriages, bride-burning, home abortions. You based that art piece on a controversial 1927 book by American historian Katherine Mayo, who had a pretty toxic worldview, and whose book many people felt unfairly attacked India. Why?

Alexander and Judy Kendall; mirrored and embroidered strips by Norma Cordiner, Sharon Fuller, Susan

Herold, Peggy Kennedy, Linda Lockyer, Lydia Ruyle. Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives

Yes, it's a flawed book, but that doesn't change that those practices existed or exist in rural India. Some of the objections are from people who don't want to deal with the uncomfortable truth.

Let's talk about your upcoming exhibit. "The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction," which will be shown in D.C. this fall.

"The End" combines painting on porcelain, glass and bronze. The first section is called "Stages of Dying," based on Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' work on death and dying. The second section is on black glass and is the "Mortality" section. It starts with bronze relief, then the next pieces are sort of philosophical musings, what people have written, going back to Aristotle, [Albert] Camus — ideas about death. Because you know, death has been dealt with just like birth historically and in different cultures. There is not a monolith of ideas.

"In the Beginning" (1982). Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives

Then it moves into a series of queries — the questions everyone asks themselves about death, such as "How will I die?" Everyone wants to die peacefully but few do.

And the last section, also on black glass, but larger, is the most difficult, and it's the section on extinction. It's a full bronze relief, which kind of brings into high relief what we're doing to other species on the planet. It took two years to do that, and the whole project took six years. I used to joke and say I was living like a nun with conjugal rights, because painting on glass, the way I do it, is very challenging and highly focused. So I would paint, exercise and rest every day, and that was about it.

What does the section on extinction explore?

It's not just what we're doing to other creatures but the scale of it. One image called "Finned" deals with the finning of sharks, [which involves slicing off a shark's fin and, often, discarding the rest]. They are finned and then left to float to the bottom of the ocean beds. They can't move and suffocate and die. We kill 100 million sharks every year, and much of it is through finning. That was just grief-inducing. And it did take a toll on me. It was probably the first time that I did a project, and had to take a break between the time I finished and showed it, because otherwise I felt I would be a blubbering idiot talking about it.

I brought all of my skills as an artist, and all of my feelings as a human being to this exhibit.

Is this the end of your work, then? Or will you keep going?

Somebody asked me if I'm going to stop, and I said: "I'll stop when I'm dead."

READ MORE: The epic, 40-year-old feminist art piece that we're still learning from today

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.