9 songs that show how people of the past coped with pandemics

"Protect me and save me," a very old song goes, "and take out of me, o martyr, the harmful weakness called epidemic."

Translated from Latin, "O Sancte Sebastian" by early Renaissance composer Guillaume Dufay calls on Saint Sebastian to save the singer from a life-threatening illness — in this case, probably the bubonic plague.

Throughout history, people have turned to music during disease outbreaks as a way to seek spiritual guidance, express pain or even educate others about hygiene. The current moment is no exception.

In recent months, artists around the world have been following this centuries-old tradition by singing about the ways the coronavirus pandemic has transformed our lives.

After rapper Cardi B posted a short video to Instagram of herself talking about the virus, and it, well, went viral, Brooklyn DJ iMarkkeyz sampled her cries of "Coronavirus!" into a popular song online.

Musicians in several African countries, including Ugandan musician and politician Bobi Wine, created a song to raise awareness about COVID-19, while U.S. artists like Bad Bunny and Gloria Estefan have released tracks about stay-at-home orders.

Others, including comedian Adam Sandler, have used music to provide some humor during quarantine. For fans of Broadway, this coronavirus remix of Les Miserables' "One Day More" may be a welcome distraction.

In light of these modern takes, we asked several historians to highlight some older songs that were born out of epidemics.

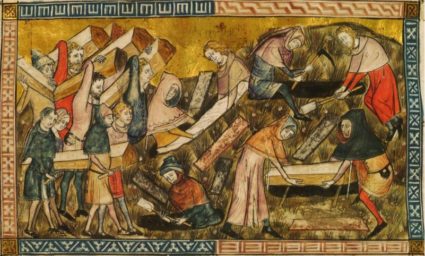

Music as medicine during the the Renaissance

Today, we often approach music as entertainment or else as austere works of art. Renaissance musicians readily recognized much broader functions for music.

For one, music was treated as a medicine that was able to temper the bodily humors, preserving or restoring a listener's health. Music was also commonly used for spiritual ends, as offerings to holy patrons, either to curry divine favors, or else to give thanks for favors received. In a society constantly threatened by plague — a biological scourge sent ultimately by a punitive God — music could be a useful double-medicine. It is likely for this reason that surviving Renaissance compositions explicitly responding to plague are overwhelmingly religious in character.

"Stella celi extirpavit" by Walter Lambe

"Stella celi extirpavit" is a hymn asking Mary to keep a hold on the stars that are killing us mortals. (Doctors thought that certain planetary alignments corrupted the air on Earth and brought about plague.) This hymn text was set to music many times, and its popularity reflects a general belief in the Virgin's role as a "clement mediatrix" who can allay the wrath of God. This hymn attracted some controversy; religious reformers thought the line "hear us, for your Son who honors you denies you nothing" exaggerated Mary's power and was therefore theologically suspect. Walter Lambe's setting, an especially sumptuous work for four voices, dates from around 1480.

"O beate Christi confessor," performed by Musica secreta and Celestial Sirens

"O beate Christi confessor," is an anonymous motet to St. Rocco, a popular saint invoked against the plague. This work was published in 1543. Like "Stella celi," this work asks the holy intercessor to undo the natural cause of plague by improving the foul air.

"Santo Guerrier" by Paolo Caracciolo

"Santo Guerrier," published in 1582, commemorates a disastrous outbreak of plague in Milan between 1576 and 1578. During this catastrophe, the citizens of Milan decided to build a new temple to Saint Sebastian, the most popular plague saint of medieval and renaissance Europe, pledged to hold annual devotions to the intercessor. This composition recollects these offerings and pledges. In a way, this work functioned as a kind of public service announcement — not unlike songs today reminding us to keep our distance or wash our hands — that reinforces the importance of vigilant piety. And it does so in a highly evocative and captivating way, too, with dissonances to depict the idea of suffering, or downward leaps to describe the fall of Milan.

— Remi Chiu, author of "Plague and Music in the Renaissance"

Got the flu pandemic blues

It is no coincidence that the 1918 influenza pandemic found cultural expression in the blues within the United States. Two songs told the story of the crisis, and in both cases viewed the catastrophe as an act of God.

"Jesus is coming soon" by Blind Willie Johnson

In "Jesus is Coming Soon," Blind Willie Johnson described a "mighty disease," an epidemic that reached indiscriminately and confounded the doctors. For Johnson, the pandemic was God's warning to Americans to "turn away from evil and seek the Lord and pray."

"The 1919 Influenza Blues," by Essie Jenkins

Essie Jenkins's "1919 Influenza Blues" shared these themes of both judgement and warning as she sang, "It was God's almighty plan/He was judging this old land." Like Johnson, Jenkins emphasized the sheer scale of the scourge and the shared helplessness of Americans as they faced the flu. "It killed the rich, killed the poor," she sang, signaling the deeper message that all would stand similarly equal before God before warning the deaths would continue, "if you don't turn away from the shame."

— Nancy Bristow, author of "American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic"

"Influenza 1918" by Reuben Tholakele Caluza

While South Africa was still under the scourge of the flu pandemic, composer Reuben Tholakele Caluza used the song "Influenza 1918" to instill a sense of direction in his South African urban black audience. The compositional style of the song is in English hymn-style four-part harmony, verse-chorus format. Caluza did two things in the song lyrics. First, he paints a picture of the impact of the disease in the African population. According to him, the epidemic decimated the elderly population as much as the youth, thus differentiating the African communities' experience from that of other global contexts in which people in their prime (ages 20 to 40) were mostly affected. Then, in Caluza's lyricism, the influenza epidemic is likened to the punishment in the biblical exodus event, which God visited upon the Hebrews for abandoning his covenant with them. Hence, Caluza calls for repentance and change in behavior, using song as his medium.

— Austin Okigbo, associate professor of ethnomusicology, University of Colorado

Framing AIDS epidemic with music

People impacted by AIDS turned to music to grieve, to remember, to celebrate, to protest, to act up and to fight back. There are literally thousands of songs about AIDS out there, and so few of them have been heard. In one of Michael Callen's songs, "How to Have Sex in an Epidemic," he says:

Where will it end my friends?

Can you tell me? Who can say?

When what is safe

and what is not

Changes day by day?

And that, to me, captures the time of COVID-19 so clearly. Information is shifting daily. People are afraid and also frustrated, but people are also using music to create community, to feel connected in this age of social isolation and distancing. There's much to learn from the music of the AIDS epidemic, structures of feeling and affect to tap into.

"Tainted Love" covered by Soft Cell

The impact HIV/AIDS had on music occurred in several distinct phases. In the first phase, people used existing music to process what was going on around them. One of the first uses of pre-existing music happened in 1985. The British industrial band Coil recorded a cover of "Tainted Love," which had been a hit for Soft Cell in 1983, but was originally recorded by Gloria Jones in 1964. The transformation of this jaunty love song into a funeral dirge really captures the affective side of the early years of AIDS, when there were no effective treatments and so little concrete scientific or medical information available. Coil also produced a stunning music video for the song, and that's really where the AIDS narrative comes to the fore.

"Living in Wartime" by Michael Callen

In a second phase, original songs about the epidemic emerged. One of the major heroes of this moment is Michael Callen. Callen used his music as part of his bigger profile as a prominent AIDS activist, and his song "Living in Wartime" captures the zeitgeist of that moment. The imagery of war is common across a lot of art and music about AIDS during this period, perhaps most famously in a couple of speeches that AIDS activist and gay film historian Vito Russo delivered at ACT UP rallies in the late '80s. But the images of war emerged early on, as People With AIDS (or PWA) fought against not only social stigma but the reluctance of the Reagan administration to do anything about the disease.

"I've Got You Under My Skin" by Neneh Cherry

The third phase involves the move into mainstream music, largely by straight artists, that began at the end of the 1980s. It seems that almost every artist recorded a song about AIDS, but very few of them released these as singles. A major exception to this are the artists who got involved in projects by Red Hot, a New York-based fundraising organization that has put out dozens of AIDS benefit compilation records since 1990. That year, they released their first album, a tribute to Cole Porter called "Red, Hot + Blue" (the plus sign is supposed to signal a "positive" HIV antibody test result). There are many incredible performances on that album, but Neneh Cherry's "I've Got You Under My Skin" takes Porter's original song and radically transforms it into a song about HIV and the impact of HIV/AIDS on injection drug users, people of color and women. It's outstanding, and the music video is so powerful.

— Matthew Jones, author of the forthcoming book "Love Don't Need a Reason: The Life and Music of Michael Callen"

MORE: A singing hospital worker and more #SongsOfComfort

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.