ABC will continue broadcasting the event until 2028, which will mark the 100th Oscars. This shift announced Wednesday represents a…

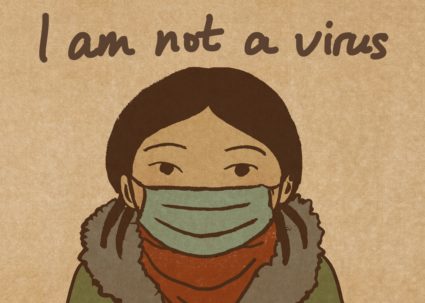

A morning commute becomes tense as an Asian girl looks up from her phone in disbelief. The white woman sitting beside her says, "Shouldn't you get off this tram?" Inspired by recent events, Korean-Swedish artist Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom is addressing the hostility Asians increasingly are facing during the COVID-19 global pandemic in a series of one-panel comics.

Sjöblom's images, shared on her Instagram account, tackle the racism directed at the Asian community since initial cases of novel coronavirus were reported late last year in Wuhan, China. The title of her series stemmed from a hashtag, #IAmNotAVirus, that was started by French Asians in response to racist incidents on public transportation and through social media. The movement has also inspired other illustrators on Instagram to create art in response.

The Asian community went "from being invisible" to being "hyper-visible, but as a virus or as a carrier of a virus," said Sjöblom.

As novel coronavirus spreads around the globe, so have xenophobic misinformation, harrassment, discrimination and insults. It's manifesting in customers disappearing from Chinatown districts in some Western countries, and aggravated assaults against the Asian community. Baseless business boycotts and vandalism have targeted other East Asian communities as well. The Stop AAPI Hate initiative has received more than 750 direct reports of discrimination against Asian Americans in the U.S., where women were three times more likely to be targeted and 61 percent of respondents were non-Chinese.

Sjöblom highlighted how racism against Asian people in the age of COVID-19 is not limited to verbal or physical attacks, but subtler actions as well.

"It's more like a feeling that you recognize when you are used to being subjected to racism, which is glances and people moving away," Sjöblom said. "You're very conscious about yourself and if you cough and you feel really surveillanced."

As a cartoonist and graphic designer, Sjöblom's work aims to broaden the representation of people of color, with a particular focus on East Asians. Her comic book memoir, "Palimpsest," follows her upbringing as a Korean adoptee in Sweden and was named one of the best graphic novels of 2019 by The Guardian. Currently, Sjöblom is working on a Swedish children's book on "the sometimes excruciating experience of being the only, or one of the few, POC [people of color] children" in a classroom and how "to make one's community understand why it's necessary to be inclusive." Her latest comic book, to be published next fall, is about three Chilean families who were illegally separated for adoption in Sweden.

The PBS NewsHour spoke with the artist, who is now based in New Zealand, about her inspiration behind the "I am not a virus" illustration series, and how to approach conversations about racism with children.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

It's a bit crazy here. We've gone into a complete lockdown. Everything is closed, and everyone is working from home. If they can't work from home, they still have to stay at home. We're in a bit of a crisis, to say the least. Hopefully, it will lead to something good in the end. But the government [has been] really great about it, I think, and our prime minister is handling it really well.

I didn't come up with the hashtag myself. I think the first time I saw it, it was actually in French. So I thought I'd join in. My Instagram account, in general, is dedicated to writing and drawing about international adoption and racism against mainly East Asians, because I'm Asian myself. So it was quite natural to bring up this issue and write and draw about it.

One of the drawings is the conversation between a white woman and a 15-year-old Asian girl in Sweden. The woman asked the girl to leave the tram, because she was Asian, so it was just based on her appearance. I read the article and I thought, that is so stupid. But instead of just writing about it, I could actually draw this thing happening. I find that a lot of things that I comment on, which are often seen as quite controversial, people tend to understand it better or show more empathy when they see my drawings.

I'm influenced by other artists who are using comics and illustrations to talk about political issues. It's everything from newspaper cartoonists to other comic book artists, like Marjane Satrapi, who did "Persepolis" for instance, who really powerfully drew about growing up in Iran and experiencing the revolution there. And of course, Art Spiegelman, who did "Maus" about the concentration camps and his father surviving them. And there are lots of other examples, where politics and comics and activism are sort of linked together in storytelling. Comics are definitely more than just superheroes, but that's not new. It's been like this for many years. Some people are still thinking that comics [are] just for children or that it's just Marvel and DC Comics. They are so much more, and I think it's a really powerful media.

The imagery that is being used and the language that's being used is not new. It's just that now, people are using coronavirus and COVID and linking the medical language to this sort of yellow humor, "yellow peril" idea and putting them together. I definitely believe that language can be used to dehumanize people and that it can cause great harm. Those of us who are activists are trying to make people aware that it always starts here with jokes and starts with harmful language. It starts with racist imagery, and the next step from that is actual violence. So Asians now are being verbally abused to actually [being] violently abused, physically abused. There's definitely a link between those things, I believe.

I haven't been subjected to it. My son has been abetted at school. As one of my drawings [is] showing too, my partner and I sat down with the kids and talked about this. There is a chance that we may be targeted. Of course, we've had this discussion many times before with them, because we were constantly targeted for being Asians when we lived in Europe. They are familiar with that and familiar that people can do bad things to us just based on our appearance. So when it happened to my son, he was very calm about it. He talked to us, and he could understand that it wasn't about him as a person, but the way he looks.

Both me and my partner, we do talk to them very clearly about what's going on. We were attacked on a bus in London a few years ago, and that was when my children were big enough to understand. We use very simple language they can understand. We say that, "If you don't look like everybody else, people might laugh at you, or think that you are wrong in some way." We also try to show them and give them good Asian role models and a variety of representation so that they can also build up some sort of self-confidence. My son, for instance, is very into football. We show him Asian football players so he can have someone to look up to that looks like him. They know that's why we left Sweden, because we felt that we couldn't really stay there. We are in contact with their school to ask them to look out for these things and to be aware. I went to their [kindergarten] to talk about positive representation and being aware of what toys they have and what books they read and that they need to include all kinds of children and not just my children.

After we had the children, because there [were] a lot of things going on, and they were quite frightening. Sweden has changed a lot, too. We have a racist party that is just growing bigger and bigger. And in general, in Europe, the extreme right-wing movements are just growing. It just feels like the climate has become a lot worse to be a person of color.

Sweden also has its own specific history when it comes to how they deal with Asian people, because the Asian population is quite small, and most of us who are Asian are adopted. We have sort of learned to internalize racism and to form this kind of "yellow humor" ourselves. And the problems are very different depending on whether you're an adoptee or not, because a lot of us grow up in completely white families and white schools and with white friends. We never learn coping mechanisms and survival strategies to deal with racism or to feel positive about the way we look.

And Sweden is actually, by law, a colorblind society. It's really hard to talk about anything involving race, because that word is not allowed to be used in Sweden. So Sweden has its problem with lack of any sort of representation. And when we have representation, it is in the form of yellow humor, yellowface, ridicule, racist stereotypes.

We felt that we don't want our kids to grow up in that kind of isolation.

So we decided to find somewhere where they are more Asians and in general better for us and for our kids. And here in Auckland, the Asian population is really big, so they blend in really nicely here. There is a lot of racism here as well, but I find that it's manageable when I compare it to Sweden.

If I look at just what's happening right now, I'm worried that they don't have anyone to talk to about things like language, if they are being teased and bullied at school or if they get those cases we talked about on the street. Because I think that for a lot of white people, in order for them to understand racist attacks, you basically have to be punched in the face and to show a bruise.

So if you say that someone moved away or someone looked angry at me when I coughed, then they can say, "Yeah, but they're probably just worried about their health. you know, in these times, people are panicking." They put the responsibility on you to be the better person and to excuse any behavior, because we can't really know if it's racism or not. But when you live with it your whole life, you kind of recognize the behavior and there's a pattern to it.

And so I'm worried about transracial adoptees, that they try to speak to their white parents or white siblings or white friends, and they are told that they are overreacting, that they're sensitive. And then, they learn that their feelings are wrong.

I'm working on a children's book which is going to deal with this issue in particular. It's a very physical way to express the feeling of wanting to be white. It's actually based on my son after the attack in London. We were there visiting my partner's family and my partner is also white. We were sitting in a cafe, and my son said to my partner, "Look around you. There are only three people here who look different and that's me and my sister and mama. Everybody else looks like you. And I wish that I could look like you." And he talked a lot about that for a long time afterwards, that he wanted to be white. So the actual thing of painting his face white has never happened. And I have never done that either. It's more a way of expressing an inner feeling of wanting to be white and to make it more direct, because people have really reacted very strongly to that image. It's more than just skin color. It isn't actually about skin color. It's about the whole idea of what whiteness is and the privileges it gives you if you're white.

If we're talking about the virus, I find it very telling that on the one hand, a lot of us in the West have been talking about the complete lack of representation, that we're completely invisible. Even in anti-racist contexts, we tend to be overlooked, but now we see us represented everywhere. So even in Sweden, which I've just said has very few Asians, even there, when they talk about people being affected by the virus [they] are still using an image of an Asian person, usually in face masks. So from being invisible, we've become hyper-visible, but as a virus or as a carrier of a virus.

And I know that a lot of black activists have been talking about the same thing, that the image of suffering people is reserved for people of color. That when white people are dying en masse, we don't get to see it as an image. It says a lot about representation and how we are using images and who is allowed to be shown as a victim or not. And the victim in this sense doesn't even need to be someone we're sympathizing with, it can be negative imagery. It says a lot about our view on Asians and it's definitely a big fail and it's also fueling racism now. And so many people are scared. So many of my Asian friends are scared of attacks.

I think that when I posted the first picture, I had maybe 3,000 followers or something, and my account was quite small. And usually, an image maybe generated 200 to 300 likes, if they were political. But then I posted that and it's been shared a lot, and a lot of people have picked it up and written about it. But it was also targeted. The first comments that came in were absolutely horrific, and I have cleaned up the commentary because there was so much racism in it.

So talking about if I've been attacked in any way, I've been attacked on my account, but not personally in that sense. I reported them all to Instagram, and then they removed them, because I still want people to feel safe to comment without being abused by other people. So first, I let them be there to illustrate what was happening and I wrote about it and then I deleted everything. But they keep coming in. But a lot of people, too, have been thanking me. I've got so many messages and just the fact that people have been sharing it really widely shows appreciation as well.

It makes me feel that it means something to people that I'm making these drawings. Especially in times like this, when you wish that you were a nurse or a doctor and that you could actually do something hands-on, I try to do what I can with the things that I have, which is making art. If people feel that I have managed to illustrate something that is important to them, that speaks to them, I have done at least something, even though I can't really save lives. People tend to go to the arts when they feel depressed or lonely or sad or for a sense of community. So apart from all the racist comments, it's been nice to hear that people are responding to the imagery that I'm doing at the moment. It makes me feel like I want to keep going.

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.