The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has just launched a 20-city U.S. tour under its new artistic director Alicia Graf…

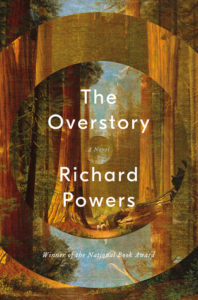

Our November pick for the PBS NewsHour-New York Times book club, "Now Read This," is Richard Powers' novel "The Overstory." Become a member of the book club by joining our Facebook group, or by signing up to our newsletter. Learn more about the book club here.

In 1854, The San Francisco Daily Chronicle expressed concern about how many trees in the region were being cut down — many of them mammoth redwoods.

"Soon the whole neighborhood will be cleared of growing timber," the paper wrote. "Already the fairest and largest trees have fallen before fire, axe, and saw."

Fast forward more than a century and a half. Author Richard Powers, who had previously written novels about music and computer science, was so moved after a walk in the redwoods that he came home and read about why much of the old-growth forests had been cut down, and why any were left.

He soon began writing "The Overstory," our November book club pick. It's a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about trees, activism, and humans' disconnect today with the natural world.

Below, Powers shares how nature has changed how he writes and lives, the importance of being present and paying attention, and what the book "Harold and the Purple Crayon" means to him.

That now depends entirely on the season and the weather! Before writing "The Overstory," I stuck to a fairly rigorous routine of starting in early after breakfast — usually around 7am — and writing until I had a thousand words that pleased me. That could take anywhere from three to 12 hours. I did that almost every weekday for a third of a century, when I had no other obligations. But research for "The Overstory" moved me to the Great Smoky Mountains, and I now have half a million acres of national park in my back yard. About a quarter of that is old-growth forest. From the spring ephemeral wildflower shows, to the spectacular winter views from the ridge trails, something astonishing is happening at some altitude of the Southern Appalachians, in every week of the year. I now build my writing around what the time and season and day are offering. I still write all the time; I just do it in those hours that make most sense, given what else life has going on at the time. As Thoreau says, "Breath the air, drink the drink, taste the fruits, live in each season as it passes. Resign yourself to the influence of the earth."

"Harold and the Purple Crayon," by Crockett Johnson. Published two years before I was born, the book was among very first stories I ever read. It gripped me then, and it has never really let me go. If you want to walk in the moonlight, you might have to draw your own moon. If you can't find a way back home, you might have to draw your own trail. I sometimes think I became a writer because of this book.

Donald Culross Peattie's "A Natural History of North American Trees" may be the most delightful introduction to the topic ever assembled. Peattie writes in the most vivid old-school way, with a flair for phrase that has by and large vanished from more recent nature writing. His stunning stories cast the history of this continent in a whole new light. Widely read at one time, these essays are now known only to a lucky few. The deep knowledge and richly engaging prose, paired with Paul Landacre's wonderful woodcuts, make this volume deeply worth rediscovery.

"Keep your petri dishes open." Alexander Fleming discovered the first known antibiotic, penicillin, when mold accidentally contaminated some compromised petri dishes full of staphylococcus bacteria. I've profited endlessly from not screwing down my plans and outlines too tightly but by leaving myself open to serendipity and happy accident. Be present, practice attention, and the story you are working on will feed on everything in front of you.

I was teaching at Stanford, in the heart of Silicon Valley. I lived within a couple of miles from the headquarters of Google, Apple, Intel, HP, Facebook, Netflix, and dozens of other companies that had created the present and were busy creating the future. When I needed to get away from that future, I would head up into the Santa Cruz mountains above the valley, where I could reconnect to the long past by hiking under the second-growth redwoods. One day I came across an escapee, a redwood that had somehow evaded the loggers when they cut down these forests to build San Francisco and lay the track for the transcontinental railroad that joined California to the East. This single monster tree was as wide as a house, as tall as a football pitch was long, and almost as old as Jesus. It struck me that Silicon Valley had sprung up down there because these gigantic trees had been up here, helpless resources to be sacrificed. The human story of that region had been written in part by these creatures who operated on an entirely different scale of time and space.

When I came down from the mountains that day, I began to read. I read how 98 percent of the old-growth redwood forests had been cut down, and that figure would have been close to 100 percent, if not for ordinary, non-political people who, only a few years ago, decided that 98 percent was enough. I went on to read over 120 books about trees. From out of this reading there grew a large, branching fable, part ancient myth and part contemporary political showdown.

I wrote and re-wrote the book over the course of several years. I would have continued to revise it had the 2016 election turned out differently. When the Trump administration began overnight to undo a half century of hard-won, bipartisan environmental protection, even opening some of the last few remnants of public old-growth forest to logging, I knew it was time to publish the book. I would happily have kept working on it for much longer, otherwise.

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.