The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has just launched a 20-city U.S. tour under its new artistic director Alicia Graf…

"What happens to people who live inside their phones?"

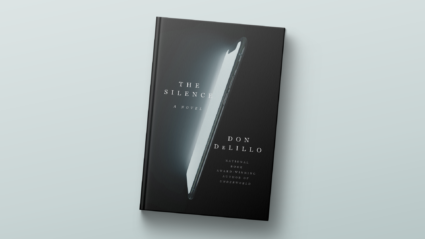

In his new novel "The Silence," Don DeLillo poses this question as screens go dark and technology fails. The story is set on Super Bowl Sunday in 2022. One couple is in flight, returning from Europe to New York. The husband, in the boredom or dream state of airline travel, reads the flight information on the screen: "Words, sentences, numbers, distance to destination."

Meanwhile, their Manhattan friends await their arrival, ready to watch the big game. In DeLillo's book, life's on a screen, many screens, constant screens. Except, when game time comes, the screen goes dark. Just our apartment, they wonder. Our building? This city? A power outage or sabotage? Is the game on somewhere? That very lack of knowing, in the short distance between us and our screens, is the space in which this novel unfolds.

DeLillo has taken us into strange places like this before. Conspiracy theories, terrorism, toxic clouds, technology gone amuck. His novels are grounded in contemporary life and culture – he can be wickedly funny on the excesses of consumerism – but the experience is somehow heightened, darker. He's been described at times as a kind of "seer" of troubles to come.

DeLillo is now 83, and while he writes up-to-the-moment stories, he seems to live, technologically-speaking, in an earlier age. He still writes on an old manual typewriter, in part he said, because he likes to see the physical letters and words on the page. He would not consent to an on-camera interview. (I've tried in the past, as well.) He rarely uses a cell phone. Instead, he called me from a landline.

DeLillo said the idea for the novel started with an image, as his work often does. In this case, it was the image of that man staring at a screen mid-flight, based on his own recent international travel.

"I began, for no special reason, to note what was on the screen, mainly factual information in French and English concerning time, air temperature, arrival time, speed, time to destination, that sort of thing," he said. He wrote about the moment in a thin notebook he travels with. "And when I got home I began to sense, for some mysterious reason I suppose, that this might lead to a piece of fiction."

DeLillo has won several literary honors, including the National Book Award ("White Noise" in 1985) and the Pen/Faulkner Award ("Mao II" in 1992). In 2013, he was the first recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, a lifetime achievement award. "The Silence" is his 18th novel. And there is some question in his mind whether there are any more to come.

I spoke with him from his home in New York.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I think it's often an image. When I started thinking about the possibility of writing something, I was on an airliner looking at a screen that was located just below the overhead luggage bin. I began for no special reason to note what was on the screen, mainly factual information in French and English concerning time, air temperature, arrival time, speed, time to destination — that sort of thing. And I wrote this in a slim notebook that I carry with me when I'm traveling, and when I got home I began to sense, for some mysterious reason I suppose, that this might lead to a piece of fiction.

Yes, it is fairly normal, I do think, in terms of images. And even when I look at the page that I'm working on, and I work on an old secondhand typewriter with larger-than-usual type, I see the words in a visual sense. I see connections between letters in a word, words in a sentence. This has been happening for some years now — I think probably when I started working on "The Names," and I started writing just one paragraph per page so I could simply see more clearly. So the eyes as well as the mind became fully engaged.

Yes, the characters are confined to an apartment in Manhattan and because the power has failed, they are limited in what they can glean from the outside world. They don't know what's happening. Apparently, nobody seems to know what's happening and all they can do is speculate. And I guess this is the reason I began to work in a somewhat stylized manner, a kind of formalized approach to this novel. One character in particular, Martin Dekker, a physics teacher, tends to make speeches, although he's not speaking to his class, his roomful of students, he's speaking to friends and acquaintances. So this simply became the predominant format of the work. And I follow along.

Yes, I did think of it that way. Or to put it perhaps more accurately I thought of it that way page by page, minute by minute, and I just kept following along. It seemed to propel itself. And I have to add that even though there was this sense of momentum, it still took me quite a long time to work on this book simply because I'm older. Not necessarily older and wiser. Just older and slower.

It was trying to get it right. It was automatic; I did not visualize a certain number of pages. It simply happened this way, as it always does. When I worked on "Underworld", a very, very long novel, I had no idea when I started that it would end up being roughly 800 pages. I follow where the momentum takes me.

I don't know if the novel does. I think life does for all of us. I don't think people can stop thinking about it. And those of us who live in the city itself, even when my wife and I take a walk, we have to be careful and avoid people without masks. I find myself walking alone sometimes like a broken field runner on a football field, avoiding certain people. On the one hand, we look forward to going out. On the other hand, it becomes somewhat problematic and occasionally is somewhat difficult.

In the early stages, perhaps, there's a kind of idea of conspiracy. But that hasn't continued. It was driven by the events of November 1963 and the assassination of the president when the idea of a possible conspiracy became very prevalent in the culture for several decades. And there was an edge of paranoia that continued to spread. Perhaps these things affected my work to a certain extent.

Yeah, technology, definitely. Even though I'm totally inept at technology, I do find it compelling. I do my best to understand it. And I do appreciate it, even though I don't use it very regularly. I just tap out words and numbers on an iPad now and then. And I'm fascinated by developments as they occur. And the question becomes, how much of this technology will be used against people in general? Whatever technology is capable of doing becomes what people use it to do, even if they're using it not necessarily to enrich themselves, they're using it because they are able to do it. That's one of the most prevalent features of contemporary technology.

It's a personal decision, and it's probably an aspect of personal inabilities along these lines. I do think about these matters, certainly, but I'm not very adept. I felt this way for decades, even when I was much younger and a bit more alert, I avoided certain aspects of technology, but I certainly did think about it and marvel at it in many ways.

No, I never lacked ambition. I'm not sure that I actually said that. If I did, I was drinking too much French wine (laughs).

I do look back, way back to my first novel, and to the fact that it took me two years of work, to even imagine that I might become a professional writer. And then the next two years of work on that same first novel, "Americana," I decided that even if I could not find a publisher for this novel, I would simply keep on going. And as it turns out, I got lucky and the first publisher to see it did take it.

I'm not sure I know the answer. It may well be that I won't be returning. But three days from now, I may get another idea. It may be a short story, it may be a novel. I honestly don't know. What I think is that I may be trying to figure out a possible volume of my nonfiction publication. But I'm not sure what's next. I have to stop talking first (laugh). That's what I have to do.

People still want to read fiction. And for that matter to read non-fiction. People want books. They want to read books. They want that three-dimensional object, I believe that's true. And, of course, many people use their screens for nearly everything, including works of literature. But because of COVID, the bookstores have been affected, obviously, along with everything else. We can only hope that when this ends, bookstores will be more active and readers will be more active in visiting bookstores. Fiction is certainly not going to disappear. The question is whether books in their current form will continue. And I believe they will. I hope they will, and I trust they will.

MORE: Could the loneliness of the pandemic facilitate a 'social revival?'

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.