They have been restored by BBC archivists and will be available next month on the broadcaster’s streaming service.

For more than two centuries, Americans have largely cast their votes on paper. Yet the paper trail of that long history is thin.

That's because U.S. law requires that ballots, a record-keeping mechanism of democracy, be destroyed after they've been used and counted in an election. It's a fraud prevention measure that formally entered the legal code in the 20th century. For federal elections, including presidential races, ballots must be stored for at least 22 months, at which point the state can decide how it disposes them. (The listed methods of destruction for California? Cut, rip or tear, shred or incinerate.)

That's why one collector of these historical documents, quoted in Alicia Yin Cheng's book "This Is What Democracy Looked Like," calls them the "most fugitive ephemera."

In her introduction, Cheng notes that, "As a material tool of democracy, the ballot should not, by its nature, be collectible." And yet, thousands of ballots can be found in ephemera collections at different libraries and museums in the country, offering a glimpse into the evolving values of our democracy at any point in time.

Cheng, a graphic designer and co-partner at MGMT. design, a studio in Brooklyn, spent time perusing these collections across the country to chart the visual history of the printed ballot back to the early 1800s in the U.S. But Cheng said her research ended up encapsulating more than just what the ballot itself looked like — they can also offer insight into the electoral process and, from a design and production standpoint, show how technological developments and ink availability shaped how they were made, she said.

"It was this kind of glorious, perfect storm of all these different conditions, societal and otherwise, that could be seen through the lens of the ballot," Cheng said.

Today's ballots reflect a dramatic shift in design that began around 1900. That was when the "blanket ballot," or "Australian ballot," was gradually installed into the U.S. voting process. At the time, it was a new format that standardized the way we voted. The ballot, distributed by the government, presents all the candidates' names in a layout that's designed to not show favor to any one candidate or party.

If the modern ballot is stripped of style — or "banal," as Cheng says in an online presentation of her discoveries and research — that's the point. Developed in South Australia in the 1850s, the blanket ballot was designed to limit voter intimidation, and more generally curb the flagrant politicking that used to surround the voting process. (Of course, the question of who can vote — and who has been historically disenfranchised — still marks the U.S. voting system.)

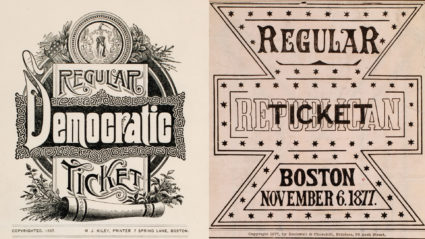

Early paper ballots in Cheng's book show how people would vote by "party tickets," or ballots that listed candidates from only one party — voters couldn't cross party lines. (The candidates listed on one 1817 "Whig Ticket" ballot were accompanied by escalating punctuation. On the ballot, George Long got five exclamation points!!!!!) With each municipality having its own requirements, some early ballots let voters write in their preferred candidates.

By the 1820s, printed ballots became much more ornate, amounting to a "typographic carnival of color and contortions," Cheng told the PBS NewsHour. There was an emphasis on standing out, either through printing on different colors of paper stock, various ink colors, expressive typography, intricate compositions with fine, engraved details. Hand-drawn names, angled and curved, take up every inch of white space on an 1864 ballot for Democratic presidential electors. At the bottom of an 1884 Democratic ticket that endorses James Buchanan for president is an instruction to verify a voter's identity: "Write your Name on the back of the Ticket."

Cheng embarked on this research after initially reading a 2008 New Yorker article that noted the use of color on old ballots. One of the collections she examined was at Southern California's Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, which is a rich resource for political ephemera. Alongside the hundreds of ballots in their collections, there are various broadsides, flyers and buttons.

Curator Krystle Satrum, who had conversations with Cheng while she did her research, said that libraries collect this type of ephemera because it can provide the broadest picture of American history that goes beyond the big names.

"The autobiography of Ben Franklin is iconic," she said. "But what's the rest of the story? Can we get information about Joe the butcher down the street? What was his story? What was his life like? How did these elections affect him? How did this election affect his daughter?"

The nature of ephemera is to be used, and usually discarded. Satrum said one of the things she enjoys about studying ephemera is that, in its way of documenting our lives, it can help fill in the gaps. These small morsels of history can deepen our understanding of what may have been lost to time and what types of conversations are still happening today.

"Who else is around? What else is there?" she added.

Before the Australian model took hold, a voter's intention would be loudly broadcast, either in paper or in person. Our earliest voting method, Cheng reminds us, was through "viva voce," or by voice. Voters — who were initially white men with property — would proudly announce their chosen candidate to a clerk, a stark contrast to the private experience we expect today. With the onset of ballots, local officials allowed parties to produce and distribute their own, making them essentially campaign propaganda.

Paper being manufactured on a larger scale gave printers an opportunity to show off their techniques. Cheng spotlights several ballots that became canvases for printers to try different designs. If the front of the ballot held the vital information, the back was a space for vibrant slogans, party emblems or other elaborate designs. The back of an 1876 Regular Republican Ticket, for example, shows two images of a clock face with times when the polls opened and closed. The designs also could help party leaders influence how people voted. Sometimes, parties used similar emblems to mislead voters who were less literate.

Behind the flamboyant ballot trend was the larger backdrop of a changing country in the first part of the 19th century. Cheng notes in her book how the U.S. population grew fourfold — from 4 million to more than 23 million by 1850. The right to vote, too, was expanded for white men. And, in this time, more government officials had to be elected to office instead of being appointed. There was also a proliferation of political parties before today's two-party system dominated U.S. politics.

But that general push to expand democracy would dissipate as the country was torn by civil war, reshaped by the abolishment of slavery, and saw millions of immigrants come to the U.S.

In Cheng's book, she explores how ballots were a way for candidates to communicate their anti-immigrant and anti-Black party platforms. A San Francisco candidate who promised to deport all Chinese immigrants within 24 hours of taking office had a ballot with racist depictions of Chinese people, including a typeface that mocks Chinese lettering. The ballot appeared years before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed, which was America's first immigration act that barred people from a specific country from entering the U.S.

An xenophobic ballot from the 1880s pushed for "protection to white labor" and "No more Chinese." An 1846 ballot, showing a racist depiction of a Black man, supports a requirement that Black men own property in order to vote in New York. And before the Australian ballot bent U.S. elections toward greater fairness, there was the blatant corruption of William "Boss" Tweed, head of New York's Tammany Hall. At the time, each ward in New York City had a boss who acted as a vote gatherer. In his 1877 testimony, Tweed made it plain how he controlled the counting of the ballots: "The ballots made no result. The counters made the result."

Cheng said it was interesting to read, amid all the endeavors to control the electorate, about the efforts to restore voting integrity.

"If the tipping point was something like Boss Tweed's demise, or something that forces the broader powers that be to affect change," she said.

Having looked at all this history, Cheng said it was inspiring "see people really believing in the power of their vote, even though there are tremendous forces that work against them."

READ MORE: Most voters expect intimidation at the polls. But they're voting in record numbers

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.