These photos helped the author of 'Heart Berries' mine her memory

Our January pick for the PBS NewsHour-New York Times book club "Now Read This" is Terese Marie Mailhot's memoir "Heart Berries." Become a member of the book club by joining our Facebook group, or by signing up to our newsletter. Learn more about the book club here.

When Terese Marie Mailhot decided to turn her personal story of growing up on British Columbia's Seabird Island into a memoir, she had to grapple with a number of significant — at times painful — memories. There were some memories, though, that she couldn't recall as easily as others. For these parts of the story, Mailhot relied on photographs.

"Photographs informed parts of the book my memory could not retrieve," said Mailhot. "I existed somewhere in a family full of secrets and unspoken histories and I felt compelled to tell those tales. Some pictures and lines from the book go together seamlessly."

Mailhot has shared some of these photos with the PBS NewsHour, along with the excerpts from the memoir they inspired.

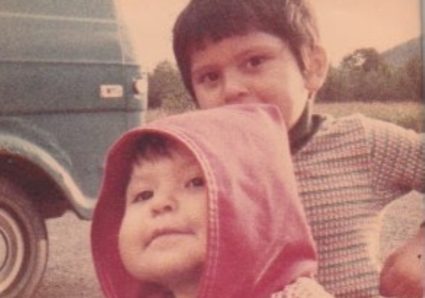

Chapter 6, "I Know I'll Go," pg 87:

"If rock is permeable in water, I wonder what that makes me in all of this? There is a picture of my brother, Ovi, and me next to Dad's van. My chin is turned up, and at the bottom of my irises there is brightness. My brother has his hand on his hip, and he looks protective standing over me. I know, without remembering clearly, that my father took this picture and that we loved each other. I don't think I can forgive myself for my compassion."

Chapter 1, "Indian Condition," pg 4:

"Indian girls can be forgotten so well they forget themselves."

Chapter 9, "Thunder Being Honey Bear," pg 113:

"I had a dog named Buddy. His fur stood up in thunderstorms. His coat was all antennae. He used to fall asleep with his nose against my skin. I never let him sleep alone in storms. He was mauled by coyotes and survived. … The dog was something good and small and the first thing in my life I could hold. I remember that I confided in him that I had been hurt. I think he was the only one I told. I thought the burden of knowing was too much, and that's why he ran away. I'm still somehow convinced."

Chapter 11, "Better Parts," pg 123:

"In the root of my mind, which is contained like our old house, and formed just so, I see you lying down against the concrete and my father standing above you. I walk backwards up the steps, knowing my feet like I never did. Do I forgive you both? We shine brighter in heaven. You are formless to me now. But, still, your pine and winter willow are in my body. As are my grandmother's olive seed and red hill earth."

Chapter 6, "I Know I'll Go," pg 86:

"I have one of his paintings in my living room. …The work is traditional and simplistic. Salish work calls for simplicity, because an animal or man should not be convoluted. My father was not a monster, although it was in his monstrous nature to leave my brother and I alone in his van while he drank at The Kent. Our breaths became visible in the cold. Ken came back to bring us fried mushrooms. We took to the bar fare like puppies to slop. His smell was not monstrous, nor the crooks of his body. The invasive thought that he died alone in a hotel room is too much. It is dangerous to think about him, as it was dangerous to have him as my father, as it is dangerous to mourn someone I fear becoming."

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.