I toured this exhibit on epidemics before the coronavirus pandemic shut it down

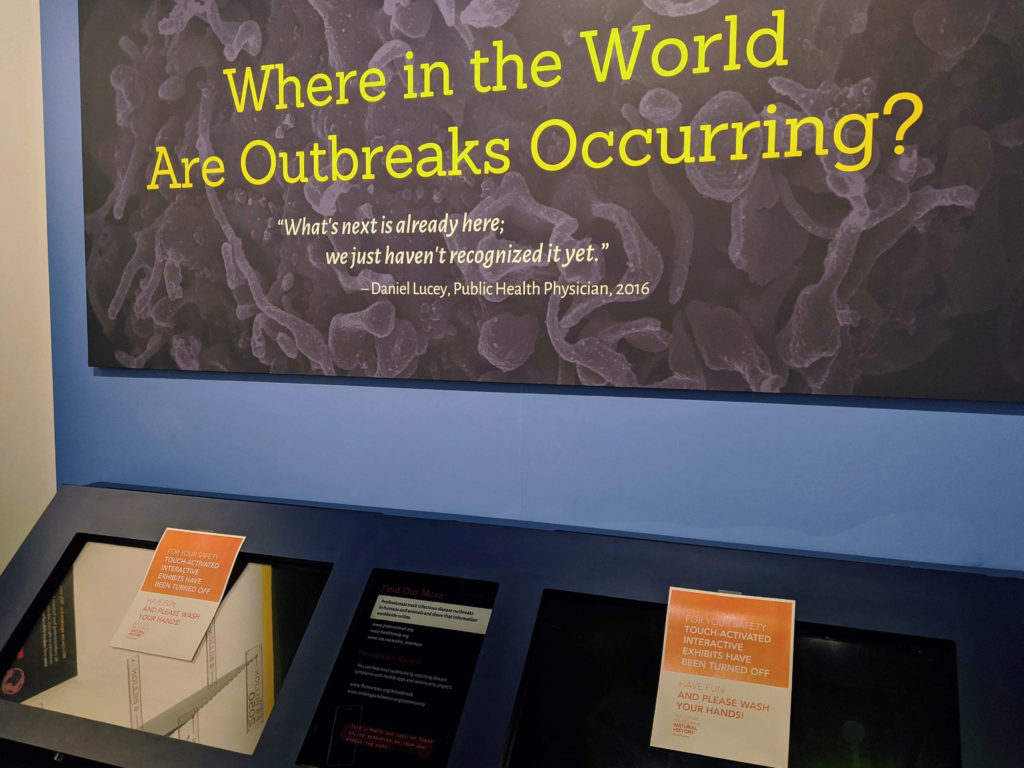

On the second floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, a placard at the end of an exhibit asks a question we all may be thinking right now, in the middle of a global health emergency: What's next?

The exhibit, "Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World," seems to have anticipated the historic moment we're living in. The next pandemic — novel coronavirus — is now here. And the exhibit, designed in part to mitigate people's fears, forces us to think about not just the alarming statistics, but also how infectious diseases emerge.

On Saturday, the many museums of the Smithsonian shut their doors to limit the spread of the virus between large groups of people. (The Smithsonian Institute has not specified a re-opening date, citing the "rapidly changing nature of the situation.") On Friday, I went to the Natural History museum — one of the world's most visited — to learn, as promised on their website, how to think like an epidemiologist.

You can take a virtual tour of the exhibit here.

That's become increasingly important, as the exhibit's placard also suggests: "What's next is already here; we just haven't recognized it yet," a quote from an infectious disease specialist reads.

Sabrina Sholts, lead curator and biologist anthropologist, said she was a "bit emotional" to see the exhibit close. We opted to not shake hands when we met.

The exhibit, Sholts said, wasn't meant to specifically tell people how to respond to a pandemic, but "hopefully delay, if not prevent something like this from happening" by increasing education and awareness.

"It was really about getting ahead of what was next," she added.

The current calls for "social distancing" are necessary, experts agree, as a means to try to contain the transmission of the virus. This conscious effort, too, has meant a halt to public life. Concerts, performances, sporting events and museums — including this one — have shuttered to prevent close contact. Many of these same spaces — long seen as a way to connect, with art and each other — have turned to live-streaming cancelled and postponed performances online, in the hopes of finding audiences there.

The museum's many interactives, which let visitors give fossilized creatures a new life or deepen understanding on a complex topic, are shut off as a precaution. The black screens look like dead pixels amid the museum's colorful displays. And taped to the blank screens are signs that remind people to "HAVE FUN AND PLEASE WASH YOUR HANDS!" Before entering, I stopped at one of the many hand sanitizer dispensers.

What I learned

The exhibit opens with a one-minute video that lays out the conditions for a new, unknown disease to emerge: As humans take up more space, we overrun wildlife habitats and increasingly expose ourselves to their pathogens. Today, viruses can also spread further and faster through modern-day international travel. The video ticks off several infectious diseases that have ravaged lives and captured attention — Zika virus, MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), AIDS, Ebola.

The music crescendos. "An outbreak anywhere is a threat everywhere," a narrator says.

The exhibit opened nearly two years ago, at the 100th anniversary of the 1918 flu pandemic, which claimed the lives of at least 50 million people. But it's not all doom and gloom. Alongside the sobering statistics is a persistent reminder in this exhibit that there are also "success stories" or ways to take action, Sholts said. Smallpox was declared eradicated after WHO led a global vaccination effort.

Dr. Daniel Lucey, a scholar of outbreaks and pandemics at Georgetown's O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, is the one who proposed the exhibit to the Smithsonian, and it's his words reminding us to think of "What's next."

In a 2018 interview with a medical association, Lucey said that the exhibit was needed because of the "harmful, excessive fear of epidemics," such as during the Ebola outbreak.

"If you look at the United States reaction to the Ebola epidemic of 2014 in contrast with the actual epidemic in West Africa, our fear was far out of proportion to the actual danger," he said.

On some displays, yellow arrows point up to "On The Upside" notes of positivity about the ways different infectious diseases were ultimately contained or treated. (A vaccine for Ebola, for instance, proved to be effective in 2016.)

The exhibit doesn't dwell on the alarming statistics as much as it does emphasize environmental interconnectedness — a call to not forget the other living things on Earth in the face of emerging infectious diseases. A quote from infectious disease expert Dennis Carroll in the exhibit drives this home: "We cannot expect to protect our own health if we are not committed to protecting the health of the ecosystems we live in."

Wildlife — especially animals who carry viruses like bats and rodents — and pathogens "are not out to get us," a statement on a wall tells visitors. Civets, mammals involved in the transmission of the virus responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), were killed en masse following an outbreak in 2004. However, evidence points to the virus originating in horseshoe bats.

It's too soon for the exhibit to weigh in on this, but experts believe that COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, i.e. one that jumped from animals to humans. For now, scientists suspect the virus originated in bats.

The stories of survivors and health care workers shared in the exhibit reveal how grim the front lines of an outbreak can be. Jackson K. P. Naimah, a physician assistant who worked at an Ebola treatment center in Liberia, is quoted as saying that every shift was horrible: "The most dangerous episode I experienced was delivering a baby from an Ebola-confirmed woman in the middle of the night shift."

A survivor of the 1918 flu pandemic, William Sardo Jr., recalled for the exhibit that when he was 6 years old, there was an "aura of constant fear." "It kept people apart … You had no community life, you had no school life, you had no church life, you had nothing … People were afraid to kiss one another, people were afraid to have anything that made contact because that's how you got the flu … It destroyed those contacts and destroyed the intimacy that existed amongst people." Sardo died in 2007.

In the current moment of crisis, there's an unease that hangs over the exhibit, despite its best efforts — and it's not the giant mosquito literally hanging overhead in the Zika section.

"Science is not leading right now"

The museum also makes plain the role that governments and international organizations play in preparing for the next outbreak. Among the helpful steps they can take: "Increase the ability for local laboratories to detect and report infectious diseases." Meanwhile, a separate placard says that "sometimes governments don't act quickly enough and health care systems can't handle these crises."

The exhibit doesn't shy away from acknowledging the U.S. government's silence in the early years of the AIDS crisis. In the absence of support, AIDS activists organized to provide care for and fight for the rights of patients instead. The iconic "Silence=Death" image — a pink triangle above the words against a black backdrop — appears on a T-shirt in the exhibit.

There's also a photo of Dr. Anthony Fauci, known for his contributions to AIDS research, as a younger man. He described how it felt like medical professionals "were swimming in the dark" when doctors started seeing the disease destroy the immune systems of gay men in New York and California in 1981.

Fauci, now the leading infectious disease expert at the National Institutes of Health, is one of the government's most recognizable experts working to fight COVID-19. He has also been forthcoming about the ways the current U.S. system for testing for the virus "is not really geared to what we need right now," calling it "a failing."

The U.S. has stumbled in its efforts to track and contain novel coronavirus inside its borders. Testing kits were not delivered when promised. As a result, public health officials say the number of known cases in the U.S. represents an undercount. Fear among the public has taken root, as daily necessities — pantry food items, hand sanitizer, prescription drugs — disappear from shelves.

Sholts said that it's still early into the pandemic, but "it's not wrong to be talking about the ways that we're failing … I mean, that's just a recognition of reality."

On the upside, Sholts said she's seen progress in the research community that has moved the U.S. fight against COVID-19 forward. But, she added, "Science is not leading right now."

In 2018, the White House dismantled a key office focused on preparing for pandemics. On Friday, the PBS NewsHour's Yamiche Alcindor asked President Donald Trump whether he accepted responsibility for that decision. After criticizing the question, he said he "didn't do it," and "I don't know anything about it."

Trump initially communicated in public statements that the outbreak could end soon. But Fauci on Friday said he can't predict when COVID-19 will peak. He said the current outbreak could last "eight or nine weeks."

"It depends how successful we are," he added.

In the Smithsonian exhibit, a 5-minute exercise involves multiple visitors working together to learn how to best respond to an outbreak. That includes sharing information, figuring out what's making people sick, and how the viral pathogen can be prevented from spreading further or coming back. For now, the screens are black.

The museum has been working on how to add novel coronavirus to the end of the exhibit. A new panel will define the new virus and nod to preliminary research about its origins. It's slated to join the exhibit in June, but that depends on what happens in the next few weeks.

After seeing Lucey's "What's next" reminder again, I catch myself consciously listening for errant coughs. Once I hear one, long after my conversation with Sholts, I leave the exhibit — stopping one final time to clean my hands.

READ MORE: 19 immersive museum exhibits you can visit from your couch

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that while civets were involved in the transmission of SARS, evidence ultimately pointed to horseshoe bats as the source.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.