How this tamales shop is keeping the tradition alive during the pandemic

DALLAS — The aroma of salty flour mix, corn husks and meat drifts all the way out to the parking lot of Dallas Tortilla and Tamale Factory, an old red brick building in Red Oak, Texas.

"It's the smell. When our guests would come in they would close their eyes, just kind of soak in the smell of the food cooking," said Lena Leal, part-manager of the shop.

Listen to KERA's story below.

Lena's family, the Leals, own three stores in North Texas: one in Red Oak, another in the Dallas neighborhood of Oak Cliff, and the other in Grand Prairie.

Pre-pandemic, Lena said people would wait up to four hours for a batch of their homemade tamales. According to her, the smell of Dallas Tortilla and Tamale Factory's tamales transport their customers back home.

"They would say, 'Oh my gosh, my grandma's house,' 'Oh my gosh, my uncle,' my — insert family relative that they remember — and that is the thing that gives my dad and I a surge," she added.

The shop has just completed its busiest season. People stock up on tamales, hoping they will last through the holidays, which in most Latinx cultures include Christmas, New Year's and Three Kings Day, a holiday celebrated the first week of January.

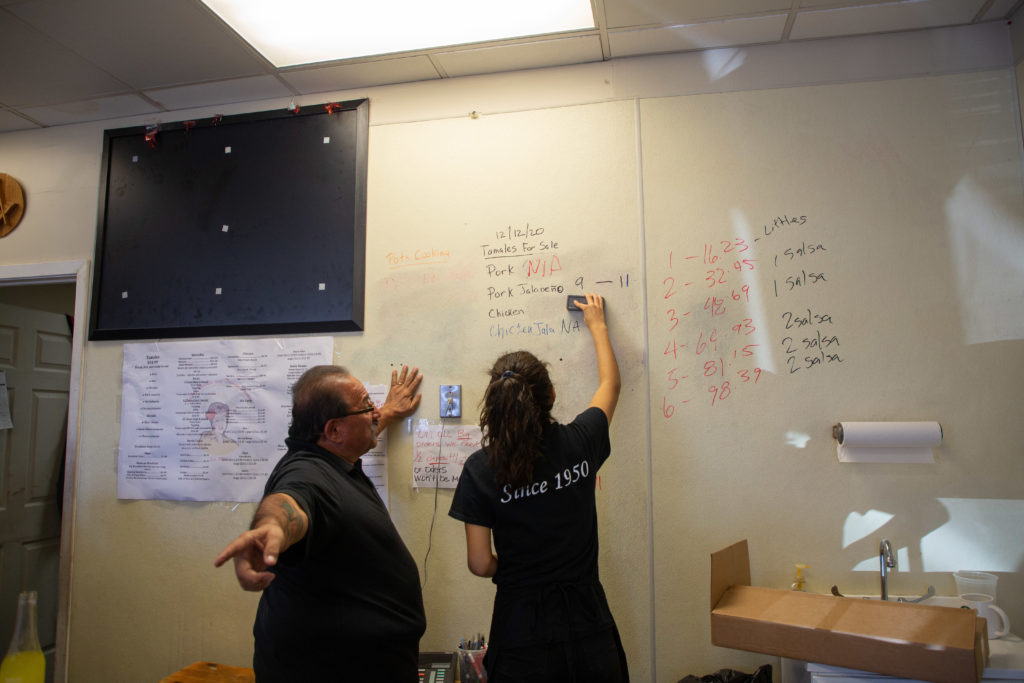

At the shop the phone rings incessantly. Workers zoom from one side of the shop and run outside to deliver tamales into cars as part of their curbside option. In the back, cooks spread the flour mix on a corn husk and stuff them with the filling as fast as possible. There are pots on top of stove tops. Most pots hold about 25 dozen and cook for about two hours.

"Pork is king but chicken has actually gained like crazy popularity in the last few years," said Lena.

The factory sells many kinds of tamales: jalapeño pork, jalapeño beef, chicken, beans and cheese and a sweet raisin. To distinguish them all, the Leal family has implemented a labeling system and placed different colored stickers on aluminum trays.

A look back at the business' seven-decade history

Most of the workers at the shop are related. Dallas Tortilla and Tamale Factory has been part of the Leal family for three generations and has a rich history.

"When people bite into our tamales, they are biting into 1950," Lena said.

The business started in Lena's grandmother's kitchen 71 years ago. While Lena's grandfather Jose Ruben was off fighting in World War II, her grandmother Elvira started making these Mexican goodies for family and friends.

"Elvira was something else," Lena said. "She ran four boys and a business all at once. She was a millionaire in the '80s, she was Hispanic, she was a woman."

When Jose Ruben returned from the war, the couple opened their first shop in what was then Dallas's Little Mexico District. At the time, the Leal family was one of the first Mexican families to start a business of its own in the city.

"One of the reasons we are so adamant about our business is because we saw my mother and my father have a hard time starting out," said Matias Leal, owner of Dallas Tortilla and Tamale Factory and Lena's father.

Elvira retired from the factory after Jose Ruben died, but the business didn't die with him. Their four sons stepped up to manage day-to-day operations, including Matias, the youngest.

"You have to think about it, a Hispanic woman starting a business in 1949 was unheard of," Matias said.

Finding Solid Ground Amid The Pandemic

According to Matias, everything cooked at Dallas Tortilla and Tamale Factory is done with a precise purpose.

"We don't just throw everything willy-nilly. We weigh everything," he said. "We cook the meat, we make the tamales, we cook the food, we cook the beans, we cook everything here."

As the pandemic unfolded, many restaurants suffered. Dining rooms were temporarily shuttered and once they were allowed to reopen, in-restaurant dining was limited. At first, this worried the Leal family, but they leaned into their to-go option of selling tamales.

"We don't have sit-down [service], so our business increased, so the other people who couldn't make it to other restaurants in this area, they came to us," Matias said.

Lena said to-go businesses are pandemic-friendly. While they saw others try to offer to-go or partner with delivery food options as a last resort, Lena said that for their customers this was just the norm. She hopes that will stay true throughout the pandemic.

For her, the shop is a place where people gather and create community. They know most of their clients by name. This year, she will take the business over from her father. She will be the first woman to run things since founder Elvira Leal.

"I would go to my parents' house every night with totals and things like that for the end of the day and I would be laughing because I cannot believe this," Lena said. "And my dad would say: 'How can you not believe it? We've been open for 70 years. Everyone knows that our light is always on."

Alejandra Martinez is a Report For America corps member and writes about the economic impact of COVID-19 on marginalized communities for KERA News.

This report originally appeared on KERA for "Report for America."

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.