For Detroit's Japanese Americans, oral histories key to preservation of history, future solidarity

DETROIT — When Mary Kamidoi and her sister were recruited from Flint Business College to work in the accounting department at Ford Motor Company in 1951, they were among the first Japanese American women to work there. They tried to buy a house in neighboring Dearborn, Michigan, the same city in which they worked, only to be blocked by racial covenants and restrictions.

Instead, they rented a series of apartments and, eventually, a house on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit. They often sat in their large picture window and noticed all the young Black people going in and out of the house next door, but never stopped to wonder what was going on. It wasn't until much later that they learned that they were living next door to "Hitsville U.S.A.," the birthplace of Motown.

Without realizing it, the Kamidoi sisters probably saw all the big Motown stars, like Diana Ross and Stevie Wonder, in the early days of their fame.

The first people of Japanese descent came to Michigan in the late 1800s, drawn to educational and work opportunities. However, it was after Japanese Americans were released from concentration camps at the end of World War II that the community really grew. Many decided not to return back to what had once been their homes on the West Coast. Rather, some decided to seek work and start new lives in other parts of the country, wherever they had connections or when people were willing to hire them. These new Japanese American communities were much smaller than those on the West Coast had been, but the challenges they faced due to racism and discrimination did not end instantly in 1945.

WATCH MORE: Revisiting Japanese internment on the 75th anniversary

The Detroit chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) has been collecting and sharing the stories of the Japanese American community in the area. These stories, spanning over a hundred years, are a vital part of Detroit's history, and similar stories can be found in communities across the country.

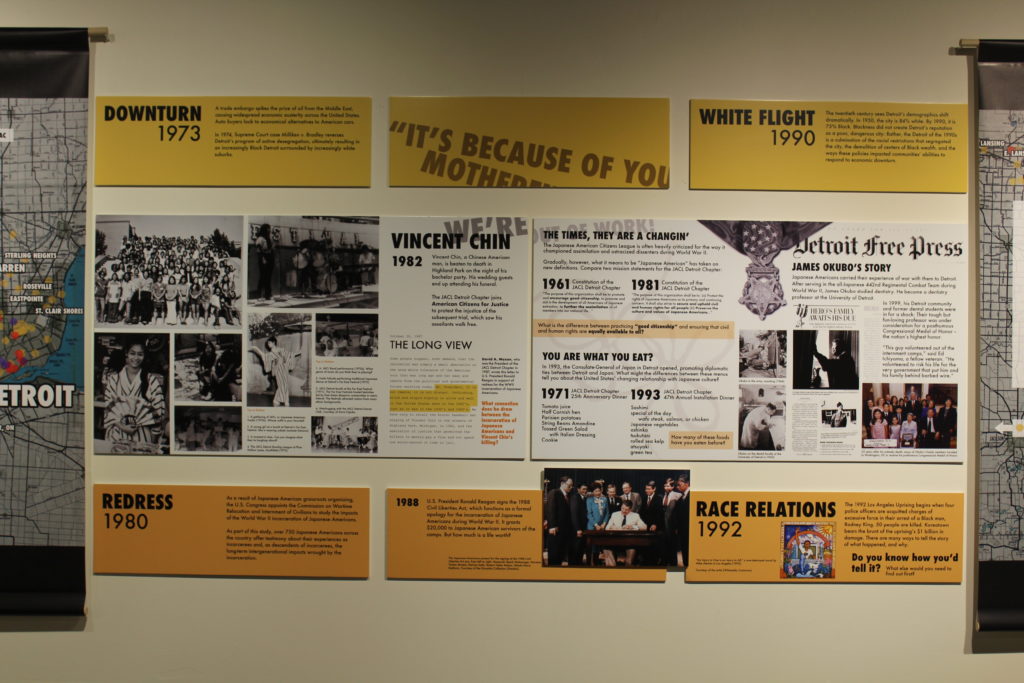

The curators of the recent "Exiled to Motown" exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum emphasize that these community stories should not be looked at as a microcosm or as a splash of local ethnic color, optional and separate from the rest of the city. Instead they should be examined as an integral part of the larger story of Detroit, and ultimately America.

"The Japanese American story in Detroit actually can't be told without thinking about its embeddedness in the city itself — thinking about the forced removal of Japanese Americans in relation to the forced removal of Indigenous peoples to build Detroit in the first place; about the ways Black bodies have been policed in terms of where they are allowed to exist and thrive in the city," Mika Kennedy, Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) Detroit chapter president, and co-curator of the "Exiled to Motown" exhibit told the PBS NewsHour. "When we take that step back, we see these same narratives — sung in a different key, but part of the same history."

A closing window of opportunity

"Exiled to Motown" began as a grassroots oral history project to collect the stories of largely second-generation Japanese American elders who had settled in the Metro Detroit area after the end of World War II.

"They had important stories that for the most part had not been fully documented or published, and there was a window of opportunity to do this that was closing," said Scott Kurashige, author of "The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles," and co-author of Grace Lee Boggs's "The Next American Revolution." "Their histories were especially relevant as Arab, Muslim, and South Asian Americans — many concentrated in metro Detroit — were targeted for racial profiling, detention, and deportation after 9/11."

With some training in how to conduct oral history interviews and how to archive photos, community members conducted interviews between 2003 and 2015, with some assistance from University of Michigan students and faculty.

"The authorship was truly collective and arose from the grassroots," Kurashige said.

READ MORE: Oregon Poet Laureate Inada Reflects on Internment

The "Exiled to Motown" book was published in 2015. "Many of the elders we interviewed or planned to interview sadly joined the ancestors before the book was published," he added.

After the book, the group created a small travelling exhibit which was displayed in several Metro Detroit libraries and classrooms, the Consulate-General of Japan in Detroit, and the JACL national convention in Salt Lake City. Curators gave presentations and organized community storytelling workshops. With each iteration, the project continues to develop.

Detroit Public Television's One Detroit spoke with the curators behind the "Exiled to Motown" exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum. Video by One Detroit

The exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum was the largest iteration yet, retelling crucial parts of Detroit's history from a Japanese American perspective. It investigates how Japanese Americans came to settle in the area; the many different types of work Japanese Americans did, including farming, retail, secretarial, automotive, translation, art, and architecture; and the many ways Japanese Americans celebrated their cultures, both deeply Japanese and deeply American, at a time when difference was not really celebrated but also could not be denied.

Being a needed ally

Masao James Hirata is the lone Japanese American man depicted in Diego Rivera's 1932 Detroit Industry murals at the Detroit Institute of Art (DIA). Twenty-seven of Rivera's murals are displayed across four walls in a prominent display at the museum. They portray, in grand scale, the geological, technological, and human history of Detroit. All the people in the murals are based on real people. Hirata can be located on the north wall, working on the assembly line with a diverse cast of workers, standing between Brown, Black, and white men.

Hirata came to Detroit before World War II. A tool-and-die worker, he later played a critical role in the production of B-24 bomber planes at Ford Motor Company's Willow Run plant, 40 minutes outside Detroit. However, during World War II, FBI agents escorted him into the building every morning, kept him under close supervision all day, and then drove him home every night.

Another early arrival was James Tadae Shimoura, who came to the U.S. in 1910 from Tokushima, Japan. While working in Pennsylvania, he was told that if he was that interested in automobiles, then he should go to Michigan to find Henry Ford himself.

"He came to the city and had the audacity to knock on the front door of Ford's personal home in search of work. He was given a job [as a chemist] and became the conduit for other Japanese immigrants to work in the auto industry as it remade Detroit and the United States," Kurashige said.

For Shimoura's great-granddaughter, Celeste Shimoura Goedert, co-curator of the "Exiled to Motown" exhibit, interest in the project was not only academic, but deeply personal. It was when her great aunt Toshiko Shimoura, a fixture of the Metro Detroit Japanese American community, died in 2015 at 88, that she learned about the book that her great aunt and Mary Kamidoi had been working on.

As a fourth generation multiracial Japanese American, a community organizer with nonprofit organization Rising Voices, and a visual artist, Goedert wanted to help expand the project because she knew how much it would mean to her family.

"Not only did I learn so much through working with the book, but in expanding the exhibit to include family heirlooms, I was able to conduct oral histories with some of my family members and hear stories and obscure family fun facts that I otherwise may not have," she said.

At the heart of the "Exiled to Motown" exhibit was an art installation that paid tribute to Goedert's aunt. Large tree branches hung with strings of tsuru – brightly colored paper origami cranes – rise up at an angle out of a black box that evokes Japanese lacquerware. The artwork was made in the style of ikebana, a traditional Japanese flower arrangement, and an artmaking tradition Goedert's aunt practiced.

The paper cranes connect the exhibit to the Tsuru for Solidarity social activism movement, which uses the healing symbolism of folding origami cranes to protest racist policies that resulted in family separation, indefinite detention, and deportation. She also created several drawings for the exhibit, inspired by wagara, traditional Japanese patterns dating back to the 8th century.

"Because so much of the genesis of Tsuru for Solidarity revolves around the crane as a uniquely Japanese American symbol of the fight for the abolition of detention," Goedert said, "We felt it would be powerful to display many cranes in an eye-catching way and hopefully entice the viewer to explore the meaning further."

The exhibit asked people to consider, "What does solidarity look like to you?" and to add their answer to a wall of colorful Post-it notes. It also invited people to fold an origami crane to send to Tsuru for Solidary to be included in future actions.

"Our history as Japanese Americans is inextricably linked with the histories of Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples and other Asian American communities," Goedert said. "In politicizing our identities and histories as Japanese Americans, we feel a deep moral responsibility to act as the allies that we needed during World War II. This spans from the fight to end deportation and detention of immigrants, and the criminalization of immigration in general, to standing with Black Americans in the fight for reparations and abolishing the carceral state.

Vincent Chin, 9/11, and a calls to action outside the Metro Detroit area

In the 1980s, Japanese car manufacturers gained greater share in the global automotive market, causing American manufacturers to lay off workers. Many Asian Americans felt the fallout. "Whenever the car slump hit the auto companies," Kamidoi said. "[Autoworkers] came to tell me that my people are taking their jobs from them. I asked, 'My people?' and "Who are you speaking of?' I was born and raised here in the United States."

WATCH MORE: 'I am an American' — George Takei on a lifetime of defying stereotypes

In 1982, a 27-year-old Chinese American man, Vincent Chin was beaten to death with a baseball bat by two white autoworkers, Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, who blamed Japan for the recession and job losses in the automotive industry. Witnesses alleged that one of the autoworkers, Ebens, said, "It's because of you little motherf–s that we are out of work." After plea bargaining the charge down from second-degree murder to manslaughter, Ebens and Nitz were convicted of manslaughter. The two men were sentenced to three years probation, fined $3000 each plus court fees, and never spent a day in jail.

Judge Charles Kaufman told the Detroit Free Press in 1983 that he gave the men such a light sentence because they had no criminal history, both had jobs, and one was also a part-time student. "I just didn't think that putting them in prison would do any good for them or for society. You don't make the punishment fit the crime; you make the punishment fit the criminal."

Outrage over the light sentence galvanized Asian Americans together nationally to form multiethnic and multiracial alliances, to organize for civil rights and change, and is often considered the start of the Asian American civil rights movement. Two federal civil rights trials and a civil suit followed; today, Ebens still owes the estate of the late Mrs. Lily Chin, Vincent Chin's mother, millions.

Goedert's uncle, Jim Shimoura, was one of the attorneys who helped found American Citizens for Justice (ACJ), a nonprofit Asian American civil rights organization that sought federal prosecution of Chin's killers for civil rights violations, the first time that an Asian American and an immigrant was considered under US civil rights laws.

"[Vincent] Chin's murder is entangled in this narrative of Japan-bashing and the encroachment of the Japanese auto industry on Detroit's auto industry. Chin is not an economic recession. He's not an automotive industry. He's not even of Japanese descent, yet he still gets caught in the crossfire," Kennedy said. "To understand that racialized violence and white supremacy are nonspecific in their impacts, I think, requires that we turn around and realize that the things that we fight for — the people and communities we fight for — need to be just as broad."

Looking at the way that the Japanese American experience is interwoven with other communities, historical events, and even changing stereotypes, the experience of incarceration during World War II led many Japanese Americans to stand up and speak out against the poor treatment of Muslim, Arab, and South Asian Americans after the 9/11 attacks, especially in the Metro Detroit area.

Of critical importance was the story of Norman Mineta, who had been incarcerated as a child with his family during World War II and was Transportation Secretary on Sept. 11, 2001. When U.S. Rep. and minority whip David Bonior said at a Cabinet meeting on Sept. 12 that Michigan's large population of Arab Americans were concerned about some of the security measures that were being discussed, Mineta recalled that President George W. Bush said, "We want to make sure that what happened to Norm in 1942 doesn't happen today."

Norman Mineta recalls the Cabinet meeting the day after 9/11

"Many Japanese American organizations and individuals also felt a particular moral responsibility to speak out and stand in support of Arab and Muslim Americans as well as Sikh Americans," Kennedy said. "Because Metro Detroit's Arab American population is the largest in the country, … I feel like these resonances feel especially clear. It's close to home in that way."

The Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles also helped support the development of the Arab American National Museum (AANM) in Dearborn after 9/11. The two institutions consider themselves sister museums. Longtime activist and "Star Trek" actor George Takei, who was incarcerated with his family during World War II, sits on the boards of both museums and has traveled to Dearborn for events.

READ MORE: The only Arab American museum in the nation is 'much more than a building'

Next summer, for the 40th commemoration of the killing of Vincent Chin, Asian American performance collaborative IS/LAND will be presenting a performance of sound, music, poetry, dance, and installation art in Detroit as a meditation on intergenerational healing. This performance will interweave spoken testimonials by Japanese American women who were incarcerated in concentration camps during World War II with the reflective movements of the IS/LAND dancers, and Goedert's Tsuru for Solidarity ikebana sculpture will also appear with origami cranes adorning it.

"These women's stories of resilience and survival, in the face of anti-Asian bigotry and a restrictive patriarchal society, spotlight how far Asian American women's roles in American society have both progressed and yet remained stagnant," IS/LAND co-founder and composer Chien-An Yuan told the NewsHour.

The "Exiled to Motown" curators are looking for a permanent home for the exhibit as well as have it travel to more cities. They are also developing a virtual version of the exhibit."Exiled to Motown" shows how Japanese Americans are more than a story of a community buffeted by world events. It is the story of how that community also shaped the world and the other communities around it. It is not just a Japanese American story, it is a Detroit story, too.

"This story connects to the broader, contested history of Detroit as a progressive site of civil rights and inclusion of communities of color versus its tragic past rife with racial segregation and white supremacist violence," Kurashige said. "It is particularly necessary to make sense of Japanese and Asian American history not only with relation to whiteness but also as it relates to Black history, culture, and politics."

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.