This artist asks how we can come out of the pandemic 'better than we went in'

DULUTH, Minn. — Workers take every precaution to keep themselves and others safe from the coronavirus in Carolyn Olson's pastel drawings.

Farmworkers wear face masks and gloves while picking vegetables and fruits. A grocery store worker wipes down shopping carts with disinfectant. A janitor pushes a cleaning cart full of supplies past doctors and nurses at a hospital. Since March, the artist from Duluth, Minnesota, has been paying tribute to all kinds of workers deemed essential during the pandemic.

For their sake, Olson wants the rest of us to do better.

These same workers, unable to work from home, have to come into close contact with scores of people every day. And social distancing isn't always an option, depending on the work site. In Olson's first drawing in the series, a child, also wearing gloves and a mask, is within touching distance of a grocery store cashier.

For months, labor advocates have raised alarms about the ways essential workers face heightened risks because of exposure to the virus, but also from complications that could arise from low wages and lack of affordable health insurance.

Olson, a recently retired public school teacher, said the series was inspired by conversations with her two children — one a grocery store cashier, the other a middle school music teacher — about how they are navigating the risks of exposure. Her son, the teacher, is able to stay home from school, but also works at a restaurant and bar as another source of income. That business plans on reopening in June.

"As a parent, I'm just panicked about my kids and panicked about the neighbor's kids. That's no way to live," she told the PBS NewsHour.

That anxiety helped fuel her desire to capture workers' stories, heard from family and friends or the news. There are so many stories that Olson, a longtime painter, turned into pastels, partly because she's able to produce more images more quickly than if she were working with oil or gouache.

Olson said her work recalls the style of two narrative artists: Swedish artist Carl Larsson, whose oil and watercolor paintings focused on the intimate details of everyday family life, and Jacob Lawrence, who captured American "builders," bold in shape and colors. Lawrence, too, is known for drawing attention to the racial disparities experienced by African American communities. The "Builders" series, in particular, pushed the idea that "we have to build our families, our communities," Olson said. "We have to do that together."

The Minnesota Historical Society, which has been collecting pandemic stories as part of its efforts to document this moment in American life, purchased Olson's first drawing, a grocery store scene, that was directly inspired by her daughter's job as a cashier in Minneapolis.

The PBS NewsHour spoke with Olson on the message embedded in her drawings and the hope contained in them for the future.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Before you started documenting the pandemic with drawings, what kind of paintings did you make?

I'm a narrative painter, so I've always just told stories about my community and family. It's a way of me talking about what's going on, but also trying to shape what I think should be going on. Like, parents should be helping their kids. Kids should be helping their parents. The community should be multigenerational. It should be diverse. It should be serving each other. But we should have joy. And I felt like, as an artist, what can I do to make society a better place? I just started documenting what I thought made for a good society.

I'm also trying to hone my skills. I'm trying to draw the figure as best I can to be emotive, to demonstrate — through their figure — how they're feeling. So the figures are exaggerated a little bit there. Hopefully they have a little more emotion coming out of them. We're full of emotions — rage, happiness, all of these things. How do you show that? We show it in our body all the time.

Over the years, I've always drawn people I know around me. I've also used it as a way to say, "Is this what you're saying?" I lived in Mississippi for a while. I drew my community. "Is this what's going on?" People could say "no" or "yes." It's a way for me to ask, and trying to reflect my community in the best way I can. And I think it helps people. I think that's why the "essential workers" [series] has resonated, because alarm bells are going off every stinking day.

Your first drawing in the series is a grocery store scene. What did you want to achieve with this work?

That was a result of talking with my daughter, who works at a grocery store. She's a cashier, and we talked early on when this all started, and I said, "So, what are you doing?" And the management at the grocery store, too, every day was something new. "Today we've got gloves. Today we got plexiglass. Now we're counting people that come in." Every day, we would talk because this was completely unknown territory. Plus, we wanted to move ahead in a good way. She needs to work. And they were very upfront about how we are going to do this right. You draw what you think about. You draw those people that you love.

The other thing is: I'm home. What does it look like? I can't go there. They're two and a half hours away. So, I imagine what she's going through, what it's like people coming through. I did another one of the grocery store, disinfecting the carts, because she came home one day, and she called me. She said, "My arms are killing me. All I did was wipe things down constantly. Every half hour, wiping something down." It was before the plexiglass went up. I drew that first one trying to figure out what [she] was going through. Where is she? What is she doing? And I also wanted to show that there's some hope, there's some happiness in that image as well. It's not all drudgery. It's vibrant. And people are together, and they're still spacey, and they're still happy, and they're still themselves. But they all got masks and gloves.

There have been attempts to capture how much the pandemic affects everyone. Your drawings center the workers themselves. Can you talk about why it was important to you to draw those stories out?

I made some limitations specifically, like you're suggesting here. I wanted to make sure that the essential workers I'm talking about are face-to-face with the general public and that that is their given job. And I do not mean to belittle the person working in a cubicle, but they're safer.

I needed to do something, and spinning in anxiety isn't gonna fix it. What can I do? What are each one of us supposed to do? How do I make a change for the better? Not every artist does it this way. Artists do it in other ways, too. I don't mean to say this is the only way to do it, but for me, it was something I could do: Draw attention to somebody that maybe wasn't getting drawn attention to.

As a parent of an essential worker, how do you feel about the general praise that's given to them?

I think a lot about the hospital workers, because growing up, a lot of us worked food service at the [local] hospital. The laundry workers, the janitors. These are people wiping up after the chaos. And these people are not making a great wage. So it does come down to quality of life. What are we saying for essential workers? These people are probably not being paid well. They probably live in not affordable housing. They live paycheck to paycheck. They don't have decent health care. There's stresses of their own family. They live in multigenerational housing where you've got old and young. How do you keep your family safe? And family isn't the only thing. I see more humanity coming, and I knew it was there. You hear all this hate, but I know people are good people. Majority of people are wanting to stay home more. Majority of people are trying to keep their neighbors safe.

When Wisconsin — we're right on the border — and when they opened up, my other child is a teacher, middle school band and waiting tables at night — when they opened up Wisconsin, he just said, "Mom, did you see it? Because they're going to open up in Minnesota." And I said, "What are you going to do?" And, you know, my chatty little teacher is very quiet about this. It's nerve-wracking because what's going to walk through the door? It's a very somber conversation. It's just worrisome.

Who do you want to hear the message in your drawings?

I'd sure like the government to consider [additional benefits and protections]. I don't see them even paying attention. I know there's people out there [in the government] paying attention, but I'm not seeing it affecting everyday people I see. I don't know why you have to have that much money or that much power when this many people are struggling. It doesn't make sense. I don't know that [government officials] care to hear from me, but that doesn't mean we don't start saying it out loud so that others know that they're not alone.

You said you instill your drawings with hope. Can you talk about your latest works and how hope is being represented?

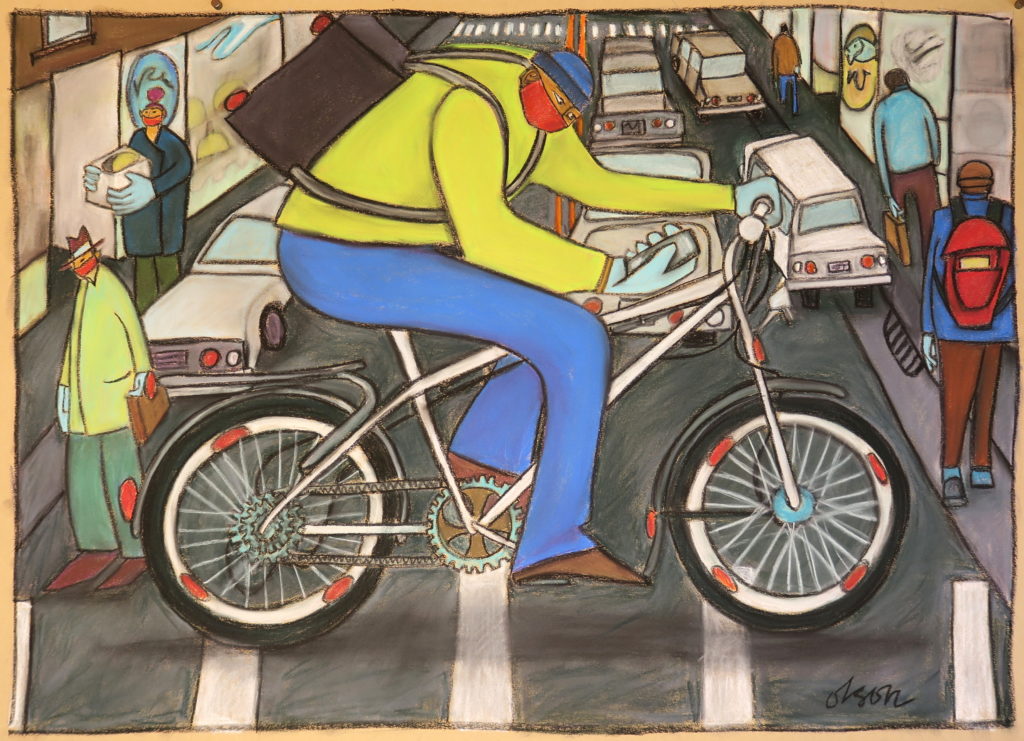

This latest one I'm working on is a bike messenger. My friend's daughter is a bike messenger delivery person in New York City. She delivers for one of the restaurants. Drives me crazy the fact that she's been doing this the whole time. She's fine. But her mother and I talk about — "So have you talked to her? How is she?" And this is work. She's got to pay her rent. [In the drawing,] the bike is huge. The whole landscape behind is off kilter. It's out of proportion, but it's really fun to look at. I think about people out there doing the work that nobody else can do.

And then voting judges, the election judges. They also are essential workers in that whole issue of — elections, Wisconsin. Again, people got sick going to vote. And they wouldn't do the mail-in voting. And most election judges are retired, older people. Smart, capable, functioning, contributing members of society, and everyone that goes to vote is trying to do the same. And why we're making ourselves struggle like this — seems like we should be able to find a better solution, seems like politics is getting in the way of common sense. [Those are the] images I'm trying to wrestle with right now.

And the hope in these images …

There's hope in all of them, that this person is still able to contribute. I'm also going to always have masks, and everyone's wearing gloves. What's gonna be our new normal? How are we going to take care of each other? We still can't stay in our houses. So, how do we do this? How do we recreate society in a way that takes care of everyone? We got to come out of this better than we went in. We have to have hope where everyone can understand what they need and what they don't need. We don't need everything we think, but there are those in our society that need more than what they've got.

MORE: Chalk art reminds us that the pandemic won't last forever

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.