On Thursday, the markets had their worst day since the U.S. war in Iran began, and oil prices saw another…

Editor's note: Recognizing that artists of color face barriers in the art world, Ideastream Public Media's "Equity In Art" series seeks to amplify the work of those in Northeast Ohio. You can see all of Ideastream Public Media's features here.

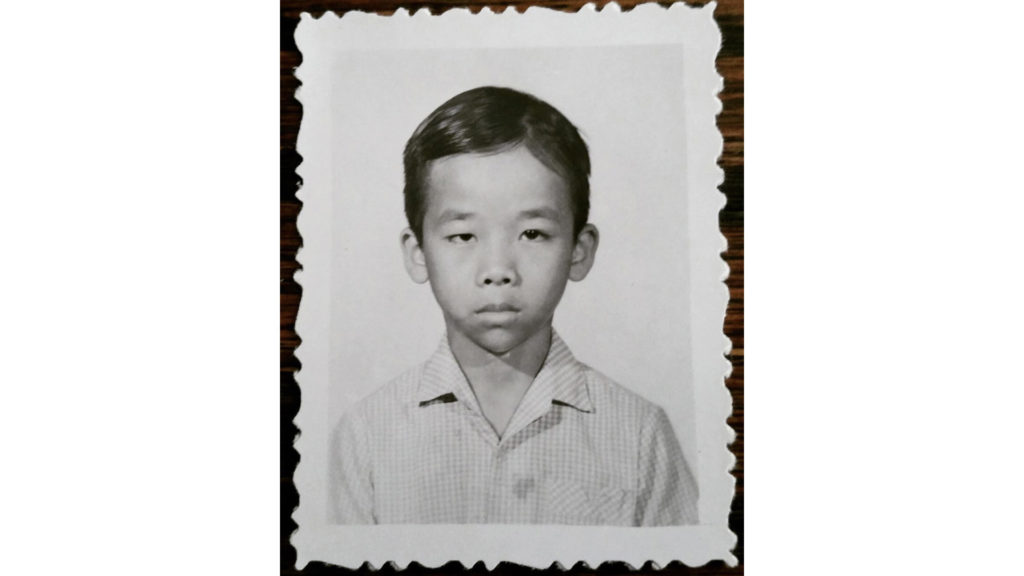

The uncertainty of life in a pandemic reminds Pipo Nguyen-duy of his childhood.

"It's like this sense of not knowing when, how, what? You know, no context in which you can embrace and understand what's going on around you," he said.

Growing up in Vietnam 50 years ago, the fear of gunfire was part of daily life. In 1975, he relocated to the U.S. as a political refugee, not knowing English and not really knowing his mother. They had lived in different cities while he was growing up, until he went to live with her in Monterey, California.

Nguyen-duy has spent his career exploring cultural uncertainties in his photography. While his projects vary, he continually considers: Where is home?

Last year, Nguyen-duy's trip to Vietnam unexpectedly extended for months due to travel restrictions forced by the global coronavirus pandemic.

He arrived at the onset of the health crisis and was directed into quarantine for 16 days in Vietnam. The dormitory-style housing was hot and full of strangers in limbo between their destinations and place of origin.

The ambiguity of the situation was familiar to the former refugee.

In both Vietnam and the U.S., Nguyen-duy said he is often seen as an outsider.

There's an irony, he said, "in returning home and only being able to look and to observe [my] culture from afar."

It's a similar feeling when he is in the U.S.

"Always there's that question … Where do I belong?" he said.

After his extended stay in Vietnam, Nguyen-duy is back in Oberlin, Ohio, teaching his photography students at Oberlin College.

Teaching, in many ways, provides a sense of home, stability and family, he said.

Nguyen-duy's career path took some big turns before he settled into teaching at Oberlin.

After receiving a bachelor's degree in economics from Carleton College in Minnesota, he moved to Northern India and learned to meditate and live as a monk.

"I did not take the final kind of vow to completely become a monk," he said. "Right before that final vow, I just decided that I needed to explore life a lot more."

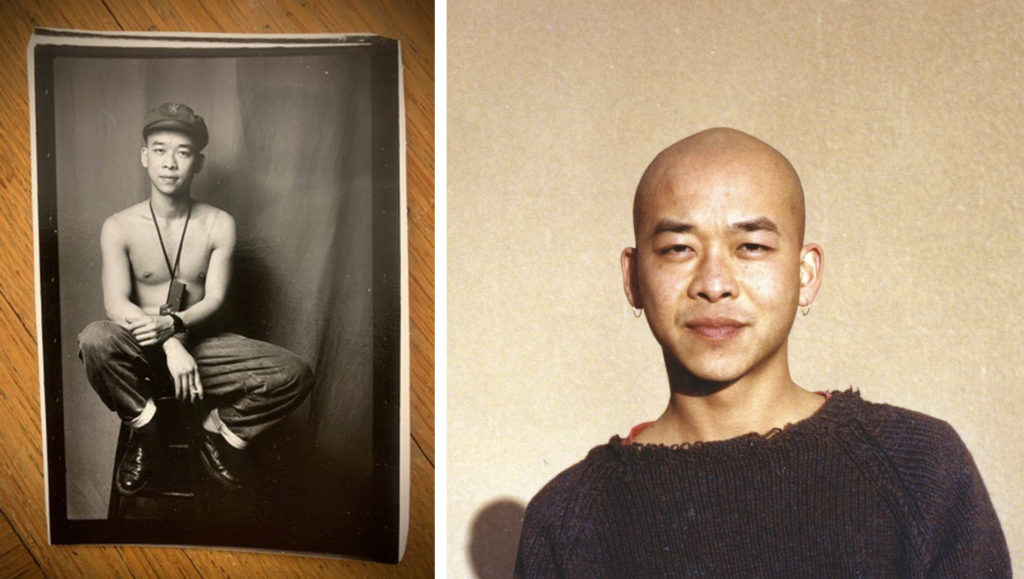

In the '80s, he moved to New York and began working as a bartender in Manhattan's East Village, bustling with artists and counterculture ideas.

Before his own art interests emerged, Nguyen-duy regularly encountered artists in the neighborhood, such as musician Don Cherry and pop artist Keith Haring.

"I was just observing, I was not doing anything that was creative," he said. "I think part of what I was doing at the time was just waiting to have a certain language, a medium in which I can communicate and tell my stories."

He also spent some time in front of the camera modeling and eventually decided to pick up a camera himself and experiment. Soon he was hooked.

"I actually quit working for a year to devote my whole time to learn photography," he said.

Even so, he said he wasn't proud of the images he was creating. In order to better understand the medium, he left New York and enrolled in graduate school at the University of New Mexico.

During his time studying photography, he said he didn't necessarily envision a career in the medium.

While working on a portrait project where he inserted himself into classical European art and Biblical stories, he began to seriously consider where photography could lead.

"I just found out my future wife is pregnant," he said. "Right after that shoot, I came into the darkroom to develop my film… asking God, 'Please give me a sign.' You know, just either I'm going to do this or I'm going to do something, I'll wait on tables or whatever, but, like, I need to support my family."

Within a few months, things started to come together for him professionally. He received awards and grant support for his photography as well as exhibitions. With his family, Nguyen-duy moved to Oregon to work and teach briefly before relocating to Ohio, where he's taught photography for two decades.

Nguyen-duy's work has also been displayed around the world in solo and group exhibitions since the '90s, including locally at SPACES Gallery and moCa, the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland.

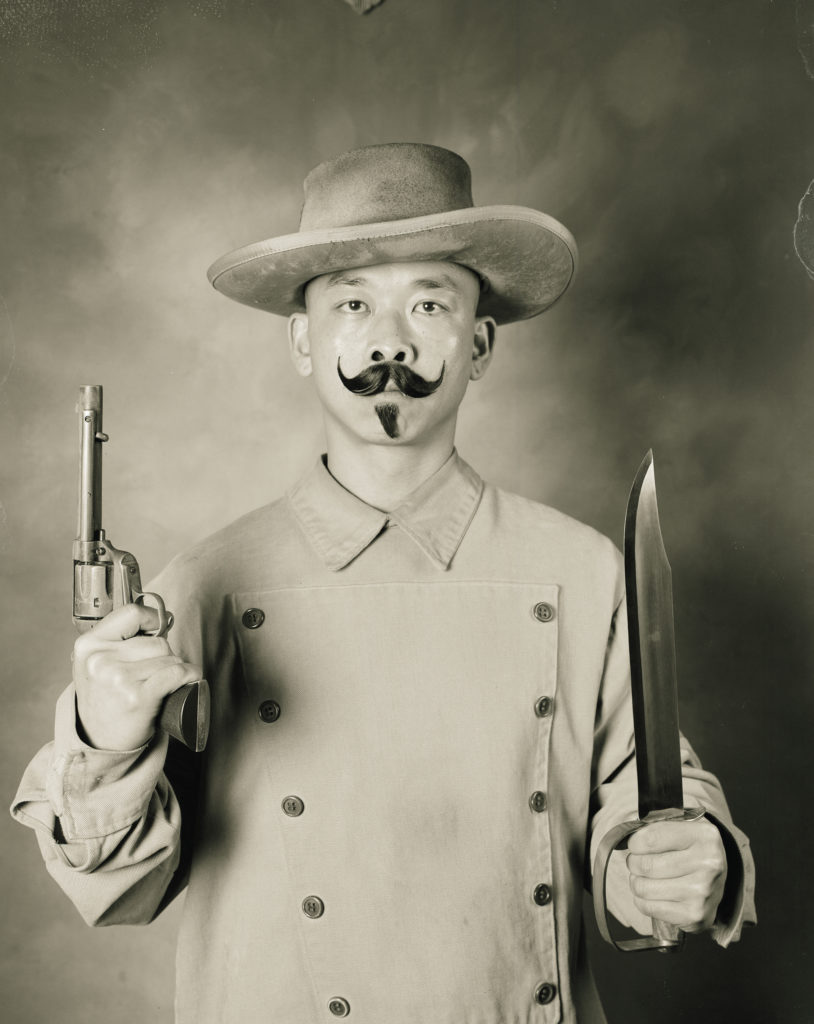

In exploring the idea of belonging in photographs, Nguyen-duy has fashioned himself as the Madonna as well as a gunslinger in the American West. He's also photographed portraits of Vietnamese amputees, maimed in war decades earlier. Some of his portraits are staged while other images are not.

A few years ago, he sat in front of a hotel room window in Vietnam for hours documenting what took place outside in an alley. Only taking breaks to eat, he described the experience as akin to a scientist gathering visual data. In this case, he was learning something about Vietnamese life from watching.

He photographed people playing cards, walking in the rain, posing for photographs and embracing on a motorcycle. Some of the images include the curtains, framing or obscuring the views.

In many ways, he experiences Vietnamese culture from an in-between state with projects like "Hotel Window."

Similarly, his self-portraits in stereotypical Western roles were a way of exploring how he physically fits into cultural narratives in the U.S.

"It really has always been about learning and about a medium in which I can engage in, that allows me to foster my growth in my own sort of creativity," Nguyen-duy said.

Admittedly, he might have gained more attention as an artist by sticking with those early self-portraits throughout his career, he said. But he's found personal growth and fulfillment by moving in different directions while still considering cultural identity.

"The nuance of and the complexities of these issues demand a different set of languages," he said.

Since 2001, Nguyen-duy has been traveling regularly to Vietnam for photography projects.

"My experience of like making work there, it's just so visceral," he said.

Nguyen-duy's work in Vietnam continues to evolve, from photographs of himself during his first return trip after leaving in 1975 to staged images with rural school kids, reflecting on his childhood memories, real or imagined.

The photographs with Vietnamese youth, captured in 2012, also express hope and resilience in a new generation.

Some of his recent photographs in Vietnam focus on rooms people rent to be intimate.

While spending time in Vietnam, he noticed large families living together in small spaces without privacy in their own homes. He also saw some couples openly kissing in public parks nearby other couples.

"And that's your private space," he said. "Yet in your private home, you can't do this."

Having also seen advertisements for hotel rooms to rent by the hour, he decided to visit and photograph them, wondering what cultural influences show up in these spaces.

He expected to see furnishings and décor centered on Eurocentric ideas about fantasy and passion. He said he did see that, for example, in a room featuring a large picture of a white couple on the wall. But another room's art highlighted a Vietnamese rice field. Another room themed around Hello Kitty gave Nguyen-duy pause.

"You have to understand, like Hello Kitty within that culture."

While he is unsure exactly when he will return to Vietnam because of the pandemic, he plans to continue to work on this project and others.

Writing down his personal stories is his next venture, he said.

Looking back at his professional experiences, Nguyen-duy said he feels blessed to have been supported in his career and to teach at Oberlin.

But it would be misguided for people to think being an artist of color has advantages, he said. There also can be an expectation for artists of color to produce work reflecting on racial identity, whether or not that is the artist's desired focus.

The murder of George Floyd by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin last summer and the Black Lives Matter movement have prompted more conversations about race in art spaces, as well as daily life.

In thinking about how things seem to be shifting as a result of these dialogues, Nguyen-duy mentioned better diversity in staffing, such as at educational institutions now paying more attention to hiring practices as a cultural response.

He also sees value in supporting a multitude of artists of color, suggesting institutions and organizations provide more grants to artists of color as well as purchasing and featuring their work.

That means looking beyond "one or two artists of color of the moment," he said. "What's going on with, like, you know, all of the rest of the artists that need to be supported, who are great, who are amazing?"

He also wants Vietnamese Americans to seek out and celebrate Vietnamese artists.

That manifests in daily life by picking up a painting by a young, Vietnamese artist at an art fair, for instance, instead of a famous, contemporary European painting, he said.

It also matters what and who is supported more broadly by anyone and everyone interested in art.

For instance, what's taught around the history of photography has been U.S. and Eurocentric, he said, missing narratives from other cultures.

"When did [photography] come to Vietnam? And where would be the general practice?" Nguyen-duy said. "A lot of these things don't get acknowledged."

He said he hopes this will change as educators and researchers of diverse backgrounds focus on histories and stories from many cultures, broadening what's shared.

"In 30 years, I think the resources will be interesting to look at," he said.

When it comes to his own art, he said he wants people to consider both the images and why he made them.

"It's not about, like, looking at the photographs," Nguyen-duy said. "But really to understand, like, who's making the photograph, who is looking through the viewfinder."

This report originally appeared on Ideastream Public Media.

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.