President Donald Trump's comments suggested that the interior of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts will be…

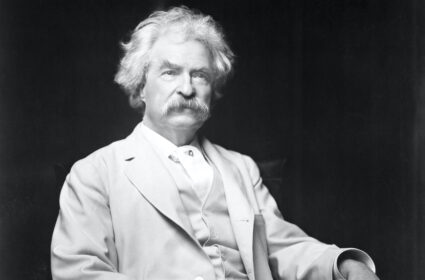

Author Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, died on this day in 1910. As a columnist who has often covered the last moments of the famous and great, this medical historian can say Clemens' death constitutes one of the weirdest life story endings I've ever heard.

The night Clemens was born, on Nov. 30, 1835, there was a brilliant view of Halley's Comet flying right over his hometown of Florida, Missouri — a sign of the bright talent he'd bring to the world. He grew up in the hamlet of Hannibal, Missouri, on the Mississippi River, that grand stream dividing the continental United States. As a boy, he spent many days having adventures outside with friends along the river and watching the steamboats pass. On other days, he preferred to sit in the office of his father, John Marshall Clemens, who was the local justice of the peace. Young Sam watched his father settle the fights of the townspeople and mete out punishment for those breaking the law. Both the courtroom and the great river made a permanent impression on the boy, and provided him with plenty of material when he later picked up his pen.

His father died of pneumonia when Clemens was 11, and he soon left school. After apprenticing at his older brother's weekly newspaper, he worked various jobs as a typesetter before training to become a river pilot. Most readers know that his pen name, Mark Twain, is an homage to the Mississippi River, referring to the depth of the river carefully measured by steamboat pilots – about two fathoms or 12 feet – that was safe enough to carry the boats and avoid running aground.

READ MORE: Why Shakespeare's own finale remains a closed book

When the Civil War broke out, the young man from a former slave-owning family served in a Confederate Army militia unit for a few weeks before deserting. As Twain, he later claimed he was too young to know the implications of joining or deserting the "Grays," but he was also fearful of being executed for desertion by his own side or worse punishments from the Union Army. To escape those risks, he fled to the Nevada territory, and later wrote a short story about this episode in his life called "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed."

In 1863, Twain got his first job as a newspaper reporter for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City. Local legend claims that the name "Mark Twain" actually came from his saloon order of two shots of whiskey at one time, with the bartender scrawling two chalk marks on the back wall under the patron's name, to mark his bar tab.

Twain's humorous newspaper articles and sketches led to better assignments detailing the exploits of the miners and pioneers, as well as a healthier salary and some national recognition. The ambitious and peripatetic Twain bounced around writing for newspapers all over the country before landing in New York City, where he pitched a story about joining an excursion to Europe and the Holy Land. His adventures on board the chartered ship Quaker City and the trail that took him to Jerusalem led to his first book, "The Innocents Abroad," one of the best-selling travel books in literary history.

Mark Twain soon became a literary celebrity, not only because of his writing but also thanks to public appearances all over the nation. He was best known as the author of "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer" and "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," which Ernest Hemingway declared the origin of modern American literature: "There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since." The book, critical of of slavery but also full of racial slurs and contradictions about race, has been frequently banned or challenged since its publication.

READ MORE: How mental health struggles wrote Ernest Hemingway's final chapter

Twain's bank account did not always correspond to his success. At the end of the 19th century, he was America's most famous writer, composing 1,000 words a day, but financially bankrupt due in part to his poor handling and investments.

During his last years, Twain began to experience crippling bouts of angina pectoris, the heavy pain in one's chest and along one's left arm that is the harbinger of clogged coronary arteries and an impending heart attack. No longer able to go out on the lecture circuit – let alone keep up his once grueling pace of writing – Twain retreated to his mansion, Stormfield, in Redding, Connecticut.

By April 1910, it was clear that he was not long for this world, and Twain took to his bed, sleeping poorly and feeling worse. The aging writer could barely raise his arms above his head to rearrange his pillows, let alone write another essay or book. On his last day of life, April 21, he was overjoyed to see the sunlight beaming into his bedroom and, for the first time in two days, he was able to sit up and converse with his family members.

Enjoying a burst of vitality, Twain asked for his copy of Thomas Carlyle's piquant history of the French Revolution, which was on his bedside table and he had been reading during his last months of life. A nurse handed him the book and, as he hoisted the heavy volume close to his face, he realized his did not have on his reading glasses. With that famous smile and the uplift of the bushy white mustache that was his facial trademark, Mark Twain tried to ask for his spectacles, but his voice was so soft and the words he uttered so slurred that she did not know what he meant. He then asked for a pencil and paper and wrote down his request. It turned out to be the last thing the great American novelist ever wrote.

A few hours later, as the next morning's New York Times reported on its front page, he "slowly put the book down with a sigh. Soon he appeared to become drowsy and settled on his pillow. Gradually he sank and settled into a lethargy…. At 3 o'clock [p.m.] he went into complete unconsciousness." The family gathered at the bedside and "at twenty-two minutes past 6 [p.m.], with the sunlight just turning red as it stole into the window in perfect silence, he breathed his last."

Now for the weird part.

After his birth coinciding with Halley's comet, Twain remained fascinated by the event for the rest of his life. In 1909 he boldly bragged to his legions of readers: "I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835; it's coming again next year [in 1910], and I expect to go out with it. It would be a great disappointment in my life if I don't. The Almighty has said, no doubt: "Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together."

Like clockwork, Halley's comet made its closest and most visible approach to the sun on April 20, 1910. And one day later, the legendary storyteller died of a heart attack.

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.