Why scholars think the unsealed T.S. Eliot letters are a big deal

Decades ago, biographer Lyndall Gordon made a vow: She would live to see the day a certain trove of T.S. Eliot's correspondence was unveiled.

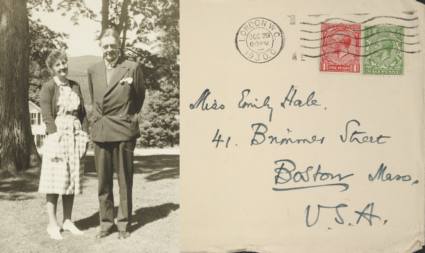

Last week, the modernist poet's letters to lifelong friend Emily Hale were opened to researchers. Eliot is regarded as one of the key American poets of the 20th century, whose work often flouted the conventions that governed traditional poetry at the time. Hale, meanwhile, is described as his "secret muse."

It will take months or years for experts to fully digest the new cache of information, every Eliot scholar who spoke with the PBS NewsHour stressed. But certain revelations popped off the page, like a clipped stanza from one of Eliot's poems.

Come join our arts Facebook group where we're discussing T.S. Eliott's letters.

In 1912, Eliot met Hale in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Years later, he began writing to her during his first (unhappy) marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, launching a rich epistolary relationship that would last more than 25 years. Later in life, Hale, a Boston-born speech and drama teacher, donated the letters she had received to Princeton University Library, but had instructed that the contents not be revealed until 50 years after they died, counting from the death of whoever lived longer. (Hale died in 1969, four years after Eliot.)

For years, scholars hoped the letters would offer a better understanding of the poet's inner life, hidden beneath his austere reserve. Eliot was a public figure who nevertheless did not want his life to be public knowledge.

Gordon, a South African-born author, first heard about the letters nearly 50 years ago, when she was writing a dissertation on Eliot's early years; since then, she has written several books about him. Last Thursday, Gordon finally got her first look at some of this private correspondence.

Gordon was among a handful of experts and journalists who arrived the first day that the Princeton University Library made publicly available more than 1,100 letters from Eliot to Hale. The letters had been kept in sealed boxes at the library's storage facility all this time. They are not available online, and must be read in person. They will enter the public domain in 2035.

Gordon began by reading the earliest correspondence available, dated 1930, found in the first of 14 boxes. It became clear, she said, how much Eliot loved Hale.

Eliot "was very emotional and very explicit about how much he loved her and how important she was to his work," she said.

But beyond Eliot's love confessions, he also wrote how his longtime friend inspired parts of his most famous and enduring works. That included the "hyacinth girl" in 1922's "The Waste Land" and the "Lady of silences" in 1930's "Ash-Wednesday." Unlike the "Easter eggs" that are sometimes hidden in movies and TV shows — winking clues dropped like bread crumbs for some keen viewer to decipher — Eliot lays it all bare. That's striking, in part, because for a long time, it was "unfashionable" to think of Eliot as a confessional poet, Gordon said.

At a certain moment on Thursday, Gordon and Frances Dickey, an associate professor at the University of Missouri, both got up from their library table, hugged each other, and squeezed hands, excited to find that the letters' contents exceeded their collective expectations.

"Not a usual scene in sober archives," Gordon later said in an email to the PBS NewsHour.

Dickey, who's been writing daily dispatches on the letters for the International T. S. Eliot Society website, described the letters as personal and detailed. In a recent dispatch, Dickey, emphasized that she's "only scratching the surface," and that it'll be difficult to say anything absolute about the letters just yet.

But the letters, Dickey said, are important because they also add to a growing body of known work from Eliot that goes beyond poetry.

"Eliot's reputation was founded on a rather small selection of poems and essays that he chose to publish, and he controlled [their] publication very tightly," she said.

But since Eliot's death, more of the poet's writing has been released, including additional volumes of letters he wrote. The letters at Princeton are the latest to be unveiled.

He actually wasn't a prolific poet, Dickey added, but "he was an incredibly prolific writer."

Gaining access to the newly public letters means that, in some ways, the study of Eliot's contribution to literature "is starting all over again," she said, "to try to assess his writing and his life and put them in context of all the materials that he produced during his lifetime."

"Eliot's writings have always been somewhat explosive," Dickey said, "but remarkably, that continues to be the case even 50 years after his death."

Eliot tries to have the last word

But Eliot had a "time bomb" for scholars, Gordon said, which detonated on the same day the letters were officially made public. That's when Harvard University's Houghton Library released a separate statement, written by Eliot in November 1960, that, as Gordon said, "exploded as planned" moments before she and other researchers were preparing to read the letters. And unlike the unrestrained musings of love in his earliest correspondence with Hale, Eliot sounded sour.

The poet said — in no uncertain terms — that he was, in fact, not in love with Hale, and counted all the ways he and Hale were unfit for one another. Eliot also wrote that he wanted to swat down any "commentary" his one-time muse may have made about their relationship.

According to Eliot, he prepared the statement — available online to read — after he had learned that Hale was giving Princeton University the letters he had written to her.

Eliot wrote that he fell in love with Hale when they met, and told her so two years later, but Hale didn't reciprocate those feelings. Eliot said they exchanged a few letters "on a purely friendly basis" while he was at Oxford. It was during that time he married Haigh-Wood.

From there, Eliot imagines — not kindly — how a relationship with Hale would have panned out.

"Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me; Vivienne nearly was the death of me, but she kept the poet alive," he wrote. "In retrospect, the nightmare agony of my seventeen years with Vivienne [Haigh-Wood] seems to me preferable to the dull misery of the mediocre teacher of philosophy which would have been the alternative."

Scholars have documented how full of anguish the marriage between Haigh-Wood and Eliot had been.

When Haigh-Wood died in 1947, "I suddenly realised that I was not in love with Emily Hale," Eliot wrote. "Gradually I came to see that I had been in love only with a memory, with the memory of the experience of having been in love with her in my youth," he added.

Eliot then wrote that he and Hale didn't have a lot in common, and that Hale is "not a lover of poetry, certainly that she was not much interested in my poetry." He later described his love for Hale as "the love of a ghost for a ghost."

And as its own paragraph, Eliot wrote, "I might mention at this point that I never at any time had any sexual relations with Emily Hale."

The 1960 statement, juxtaposed with his earliest letters, are wildly different in tone.

"It's really beneath him," Dickey said. "It's very disappointing, especially when you look at the letters."

Dickey said Eliot, in that statement, is "trying to reclaim the narrative about his life from these 1,000 letters that he knows are going to be open to the public" by belittling Hale and saying that it wasn't a significant relationship or that he outgrew it.

"The truth is, it's much more complicated than that," she said, noting that there's "so much love" in the letters, and it goes on for years.

Eliot also married his second wife, Esmé Valerie Fletcher, in 1957, a few years before he wrote that statement.

Gordon said, at that time, Eliot was "deliriously happy and so desperately in love" with Valerie. In essence, the statement was a way for Eliot to "wipe the slate clean," she said.

Gordon, too, found Eliot's statement belittling of Hale, but also said there was a "grain of truth" to his description.

"We have to think about the fact that all of us, when we're in love, there's an element of fantasy about the beloved," Gordon said. "And so, what Eliot is doing is rebranding that in a belittling way — it was a delusion, it didn't exist. And that's not true, when you read the actual letters."

"He was both a great poet, indisputably, and at the same time, flawed," she said.

Hale lets "the record speak"

In her years of research into the poet, Gordon read letters Hale wrote to her other friends. Gordon — whose book, "Eliot Among the Women," is expected in 2022 — said she has a "very consistent picture" of Hale through her writing. Gordon described Hale as someone very professional in her work and, as a drama teacher, put on excellent productions. Her pupils, whom Gordon has met, all revered her.

"She was a brilliant teacher who encouraged her girls to bear the fruit they were made to bear," Gordon said. "And she was a person of integrity, of loyal, lifelong friendships."

Like Eliot, Hale left her own personal account of their relationship as part of her donation of letters. Dickey said Hale was "pretty even-handed" in her take, noting happy milestones — and the breaks — in the friendship.

Since manuscripts of Hale's narrative can only be viewed at the library, the following details came from Dickey's reading.

Hale's account points to how they first met — "others alerted her that she was the exclusive object of Eliot's attention" — and how Eliot professed his love, but ultimately didn't propose, before leaving for Germany a couple years later.

"She found herself surprised by his confession and did not feel the same about him," Dickey wrote.

Hale said they renewed their friendship in 1922, several years after Eliot married his first wife, Vivienne Haigh-Wood. Hale said Eliot was still in love with her then.

After Haigh-Wood was committed to an asylum, Eliot frequently visited Hale when she stayed with her aunt and uncle in Chipping Campden in the summer. Nearby is the Burnt Norton manor house, whose garden was immortalized in an Eliot poem of the same name. The two had made a day trip to the manor house during one summer. Hale confirmed that Eliot told her that his "Burnt Norton" was a "love poem to her," Dickey wrote.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. My words echo

Thus, in your mind.

Hale's account says that she did start to develop feelings for Eliot, but that the two kept it "honorable." When Haigh-Wood died, Eliot didn't marry her. While she accepted Eliot's decision, Dickey wrote, she could not understand it and found it "very painful." Hale also said she didn't hear from Eliot again after he married his second wife.

According to Dickey, Hale ends her narrative by saying, "Vital Truth is a priceless heritage in the world of letters … May the record speak, all this in itself."

In a 1963 revision to his statement, Eliot wrote that Hale's letters to him "have been destroyed by a colleague at my request."

Dickey said, although Eliot stopped corresponding with Hale in the last years of his life, he can't "erase" the record of thousand letters that were sent previously.

Like his world-famous poems that articulated his deep feelings of longing, the letters, which up till now had an audience of one, "speak eloquently to the fact that he did love her for a long time," Dickey said.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.