The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has just launched a 20-city U.S. tour under its new artistic director Alicia Graf…

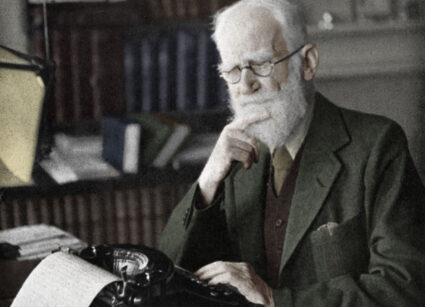

This week in 1927, the curtain fell on a Broadway production of George Bernard Shaw's medical drama, "The Doctor's Dilemma." Shaw – who is most famous for writing "Pygmalion" – was an Irishman by birth, a socialist by hard experience and a firmly committed Londoner. He wrote the play in 1905, while peeved at his own doctors and the medical profession in general.

"The Doctor's Dilemma" advocates for a socialized system of health care delivery and a removal of the profit motive from medical practice. The play dramatizes a dilemma experienced by posh physician Sir Colenso Ridgeon, who has a single dose of a curative elixir and two patients who might benefit from it. On the one hand is a gifted artist named Louis Dubedat who grifts money from his acquaintances and cheats on his loving wife Jennifer; on the other, a dedicated but poor doctor who serves the underprivileged regardless of their ability to pay. To make ethical matters worse, Colenso falls hopelessly in love with Jennifer.

Shaw pulls out all the stops with a comic situation that poses a far deeper question: How does one quantify the value of another person's life and who is even qualified to do so fairly and justly?

"The Doctor's Dilemma" first hit the boards at the Royal Court Theatre in London's storied West End on Nov. 20, 1906. The play ran for only 50 performances, at a time when a Shaw byline did not yet guarantee long lines of ticket-buyers.

Exactly 21 years later, when announcing the 1927-28 revival, The New York Times opined: "One should remember that Mr. Shaw then was not rated as he is now. His prestige has grown with the gradual whitening of his nice red beard; his fame in both England and America is now so great that any play of his is almost guaranteed a run. It was not always thus."

When Shaw complained about the commodification of health care, he was writing about cottage industries of incompetent and impotent private practitioners who did better financially by selling useless nostrums and incompetent theories. Today we see commodification in all the ways that health care is run by big industries.

READ MORE: The failed Broadway musical I wish every medical student could see

Wary of doctors of all stripes, Shaw was a strict vegetarian and vociferous health nut. Coming out of the fog of the most significant and costly pandemic of our lifetimes, we might ponder how Shaw predicted the importance of globalizing public health, fighting infectious diseases, and teaching people to live healthier lives, including better more sustainable, calorie-friendly, tobacco-, alcohol-, toxin- and drug-free diets. However, even he was not immune to the lure of a famous physician promoting his own wellness product.

While on a voyage around the world in 1936, Shaw made a special stop to Dr. John Harvey Kellogg's sanitarium in Miami Springs, Florida. The two men — one famous for developing a healthy lifestyle he called "biologic living" and co-creator of Corn Flakes, and the other the world's most famous living playwright — sat down for lunch, followed by a lengthy consultation and medical examination. Amid the flashes of photographers' cameras, the two men sipped freshly squeezed orange juice.

The following day, Kellogg reported that he was concerned about the playwright's low red blood cell count (40 percent less than normal, at 3,000,000) and hemoglobin (30 percent deficient at 71 mg/dl).

These findings were the result of Shaw's diet excluding red meat (and, hence, enough iron) in his diet. Although an increase in iron-rich, green, leafy vegetables, such as spinach, would undoubtedly help Shaw achieve a normal blood balance and feel better, the doctor advised a different, slightly shady, way to achieve those ends.

READ MORE: How Dr. Kellogg's world-renowned health spa made him a wellness titan

He prescribed his newest food invention, a product he called "Food Ferrin," which was a concentrated extract of spinach that provided a day's worth of iron in a teaspoonful or two. The alternative would be to ingest a pound of spinach each day. "I am sending you a bottle of this," Kellogg wrote Shaw, "and if you think worthwhile to make use of it, I will gladly see that you have a larger supply."

The visit — and the plug for Food Ferrin — was widely reported in publications ranging from the Miami Herald to The New York Times and the Literary Digest. The doctor stroked Shaw's ego with a prediction that he would easily live to be 100 (Shaw died in 1950 at the age of 94).

Kellogg further pontificated to the reporters recording his every word that he sincerely hoped that "my suggestions may prove of some service to the most distinguished of living Englishmen," thus presenting a new doctor's dilemma: the most marketable doctor in America giving free samples of his latest foray into fortified foods to the profession's greatest critic.

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.