In 2022, there were nearly 33,000 estimated cases and researchers project that cases will rise to more than 36,000 by…

When 16-year-old Joan Battle Valentine got word that there was a major march for jobs and freedom occurring in Washington, D.C., she knew she had to go. The native New Yorker, now 73, was a member of the Congress of Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.), a civil rights group, at the time.

"I was not that politically savvy, but I knew what I was doing with them," Valentine, who grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, recalled in a recent interview with the PBS NewsHour. She said her activism with C.O.R.E. formed the backbone of her high school experience, and she often attended protests that sought to bring attention to issues like school integration at a time when parts of the country were still deeply segregated.

But when the 1963 March on Washington rolled around, Valentine's mother didn't want her to go. "But I was active in whatever was going on in the city, so she knew I had to go," Valentine said.

Valentine ended up traveling on a bus to Washington with her mother's cousin from Long Island and a church group rather than with her friends. After hours of sitting on a bus of women singing religious songs, she said she was immediately taken aback by the scale of the event.

"When you were there in Washington, you realized how big the movement was," Valentine said. "When you got down there and saw that people were there from every state — that's what really impressed me … You know, I was never so connected."

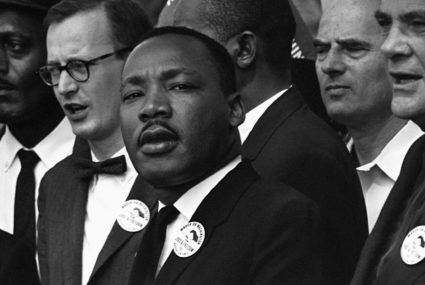

For those who attended the first March on Washington, or listened to Dr. Martin Luther King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech from their radios and televisions, the event was seen as a watershed moment for the civil rights movement. In the years that followed, landmark legislation was passed — including the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act — that moved the needle for racial justice in the United States.

But 57 years later, racial inequities still persist in America, and many have come to the fore amid a pandemic that has disproportionately affected communities of color and a string of recent incidents in which Black men and women were shot or killed by police.

The growing unrest fueled this year's March on Washington events on Aug. 28. The largest gathering, organized by the Rev. Al Sharpton, was called "Get Your Knee Off Our Necks" — a reference to George Floyd, a Black man who was killed by a Minnesota police officer who kneeled on his neck for more than 8 minutes. As thousands of attendees gathered in Washington to protest police brutality, activists reflected on the march in 1963 and how it informs the fight for racial justice today.

Just as 2020 feels like a moment of national reckoning on racial injustice, 1963 was a "pivotal" year for the civil rights movement, said Damion Thomas, a curator with the National Museum of African-American History.

Prior to the first March on Washington, Martin Luther King, Jr. and several civil rights organizations led a campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, to dismantle the city's segregation system through sit-ins at lunch counters, marches and a boycott of local businesses. Their efforts resulted in the removal of "White Only" and "Black Only" signs from drinking fountains and restrooms, as well as the desegregation of lunch counters and the creation of a jobs program for Black residents.

"Certainly when you think about Birmingham, which had been a tremendous success in terms of desegregating society, that was a watershed moment," Thomas said, adding that the labor movement was pivotal to the march as well. "There are a number of factors which led to this being much larger than I think people originally thought it would be."

Although the Birmingham campaign that took place in April and May of that year was ultimately seen as a success for the civil rights movement, the demonstrators had faced widespread violence, as police unleashed fire hoses and dogs on the crowds. Images of the violence played out on television and in newspapers, bringing international attention to the cause.

"What we start to do, particularly after the brutality of fire hoses and police dogs in Birmingham — we were trying to frame the question, 'What kind of country are we? Don't we want to move forward from this because we are better than this?'" Clarence B. Jones, once King's lawyer and adviser, recalled in a recent interview with the PBS NewsHour.

Jones was with King and other organizers at the Willard Hotel on the Tuesday night before the 1963 March on Washington. While King had been thinking about the speech since June, it was still unclear what he would say to the crowd the next day.

"Knowing him, I know that the point of departure, where to start, sometimes was a challenge," Jones said. He offered King notes, handwritten on a yellow sheet of paper, where he had made some suggestions for framing the opening of the speech. Jones didn't give it another thought until the next day, when he heard King use his notes to inform the opening paragraphs of his speech.

"As I'm listening to him speak…he is actually repeating the words which I had written — the first seven paragraphs," Jones said.

But for Jones, the memorable part came when King moved past the opening of the speech into a sermon-like delivery of his broader message. "I said to someone sitting next to me … 'these people out there don't know it, but they're about ready to go to church,'" Jones recalled. With encouragement from gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who urged King to tell the audience "about the dream," the civil rights leader articulated his vision for an America free of racial division and tensions in what would become one of the most famous speeches in American history.

"What King was able to do in that speech was to situate the civil rights movement within the larger trajectory of the American narrative about who we are, and what we value and what's important," Damion Thompson of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

An estimated 250,000 people were in attendance that day, a crowd that Jones said was unprecedented at the time.

"When we got to Washington, I was really overwhelmed by the number of people who were there," said 74-year-old Jerome Dawkins, who traveled with two friends from Linconia, Pennsylvania, to attend. "I never saw that many busses at one event in my life." He added of hearing King speak, "I recognized that this man was exceptional."

Seventy-six year-old Betty Jones attended the March on Washington, but does not remember hearing King's speech well. "You could not hear or see well because of where we were situated in the crowd," Jones recalled in an interview with the NewsHour. But she quickly realized she was witnessing a historic moment.

At the time, Jones had been working to desegregate movie theaters in Salisbury, North Carolina, where she attended school at Livingstone College. Although she didn't notice a change overnight after the March on Washington, she did see that gradually the event "inspired more people to get actively involved in the cause."

Those who attended the 1963 March on Washington witnessed the achievements, but also the setbacks that came after. Although two key pieces of legislation for racial equality — the Voting Rights and Civil Rights Act — were passed in the years that followed the March on Washington, King was assassinated in 1968, and protests erupted throughout the country. That same year, a report was released by the Kerner Commission, a presidential commission created to investigate the motives of the 1967 "race riots," which found that discriminatory practices in policing, criminal justice, housing, and other sectors of society were perpetuating poverty and institutional racism in American cities.

Today, many of the issues that Black activists are fighting for, including economic equity and voter access, align with the "Ten Demands" that the organizers of the March on Washington proposed in 1963.

For Clarence Jones, the pattern of police brutality seen in the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and most recently the shooting of Jacob Blake, is nothing new. King, after all, addressed police brutality in his 1963 speech, in which he said "We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality."

"The Black Lives Matter movement is a historical validation of both the success and the failures of the March on Washington," Jones said, referring to the movement that is driving much of the protests against racial injustice today. Jones and surviving civil rights colleagues issued a statement on Friday affirming their support for youth-led movements like Black Lives Matter and made a renewed call to address economic justice and voting rights, as well as newer threats such as climate change.

There are notable differences between the way today's young Black activists organize compared to their predecessors. "The leaders of Black Lives Matter are very conscious not just of the short-comings of policies that didn't get enacted or fully implemented as a result of the civil rights movement, but they're also cognizant of what they perceive to be the blind spots of the civil rights movement," said Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory University. She added that the Black Lives Matter movement, which was started in 2013, has made an effort to move away from some of the "patriarchal, "top-down," "heteronormative" standards of the civil rights movement by amplifying more LGBTQ, female and marginalized voices.

Gillespie also added that today's Black activists have tended to steer away from the "cult of personality" that surrounded some of the most prominent civil rights leaders in the 1960s.

"Organizers of this particular movement have attempted to remain decentralized," Damion Thomas said. "That's an important development in how people organize in the 21st century." But he added that although the history of the civil rights movement has been told through the lens of its leaders, big moments like the March on Washington were still "the seeds of smaller, community-based movements."

Whatever their approach, said Gillespie, movements for racial justice do not operate in a vacuum. "It's important to understand that you usually see multiple generations involved in civil rights struggles," Gillespie said. "Younger people are the ones who put their bodies on the lines, but it's a multi-generational movement."

"I think in 1963, people were very outraged, and they did not hide their feelings. And for so many years after that, people started hiding their feelings. But for some reason in recent years I think those feelings have started resurfacing again. It's unfortunate, but I'm reminded of what it was like back in 1963," Betty Jones said of recent racial unrest. She added, though, that she was heartened to see "so many young people stepping up" to protest in recent weeks.

"When I see those young people, and I see what they are doing with Black Lives Matter, this tough old dinosaur, it brings tears to my eyes, because I see that they have developed a vision and a courage," Clarence Jones said. Whatever differences there are between today's young activists and his own generation, Jones said, "If [Martin Luther King, Jr.] were alive, he'd be so so proud. He would be among the first to applaud what they're doing."

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.